The Elektra Story

The Elektra StoryElektra Records was started by Jac Holzman in December, 1950, in New York City. Elektra initially

recorded folk music, ethnic music, jazz and gospel, although it later expanded into blues, pop, and rock

music.

Jack Holzman was born in September 1931 on the Upper East Side of New York to upper middle class

parents. His father was a successful doctor. Jac Holzman rebelled against his parents' life style and ran

away from home many times. When he was 12 years old, he got as far as Trenton, New Jersey, and

holed up in a hotel room but was found and taken home. His parents did have state-of-the-art

phonograph

equipment, and Jac wrapped himself up in music and radio. His grandmother was Estelle Stenberger

who

was the head of the National Council of Jewish Women and did political commentary on radio station

WQXR. Jac would frequently go with his grandmother to the station for her radio broadcasts, where he

became interested in radio. He began to experiment with electronics by building crystal radio sets. This

activity stopped when his parents shipped him off to the Peekskill Military Academy for two years. In

1946,

he successfully pestered his father for a Meissner semi-professional disc recorder for his fifteenth

birthday, which he used to record bar mitzvahs and weddings.

Jac graduated from high school at sixteen and entered St. John's College in Annapolis, Maryland. He

pretty much ignored his school work, missing most of his classes. St. John's had an electronics lab

where

Jac would hang out working with electronic equipment. In the early fall of 1950, Jac attended a recital at

St. John's by soprano Georgianna Banister. The recital featured musical settings of poems by Rilke,

Holderlin and e.e. cummings, accompanied by the music's composer, John Gruen. Jac felt the music

was

worth recording so Jac decided to start a record company and do it himself. Holzman asked Banister

and

Gruen to record for this non-existent record company. On October 10, 1950, Jac decided to use the

name

Elektra for his company and in December 1950 recorded New Songs By John Gruen in one three

hour session at Peter Bartok's recording studio in New York City. Jac took the tapes to RCA for

mastering

and pressing. He received the test pressings in February, 1951, but was disappointed to find the music

was barely audible above the surface noise. He complained to RCA and they agreed to do another

transfer, so Jac went from St. John's to New York to supervise. This effort was successful and in March,

1951, Jac received 500 copies of Elektra EKLP-1. Jac found a national distributor who agreed to take

100

records, but demanded 50 additional free copies for "promotional purposes". By the fall of 1951, the

distributor returned all 100 records, the only records sold came out of the 50 freebies. So far, Elektra

was

a money-losing venture.

After his junior year, the acting Dean of St. John's "suggested" that Jac take time off before starting his

senior year to get his bearings. His parents were upset, but Jac moved back to New York and settled in

Greenwich Village. He took a five dollar a week walk-up at 40 Grove Street. In order to make ends meet,

Jack started a record store at 189 West 10th Street which he named "The Record Loft". He had about

1000 records for sale, of which 400 were folk music titles. Many of the folkies living in Greenwich Village

would stop into the store just to browse and talk music. One day, George Pickow came into the store

and

mentioned that his wife was a folk singer (he was married to Kentucky folk singer Jean Ritchie). Jac was

impressed with Ritchie, and decided to record her. Because Jac Holzman was still under 21, his father

had to co-sign the contract. The second Elektra LP [EKLP-2] was a 10 inch album with the unwieldy title

Jean Ritchie Singing the Traditional Songs of Her Kentucky Mountain Family. The record

received

great review,s and Jac predicted in a letter to Ritchie that it would eventually sell 2000 copies.

Elektra Records was off and running, and after the success of the Ritchie album, Jac purchased his own

recording equipment. He bought a Magnecord PT-6 tape machine with an Electro-Voice Hammerhead

microphone. Elektra continued to release folk albums with records by Frank Warner, Shep Ginandes,

Cynthia Gooding, Hally Wood and Tom Paley in 1952 and 1953. In 1954, Elektra issued it's first blues

albums, two by Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. In 1954, with eight records released, Jac closed the

Record Loft and moved Elektra to larger offices at 361 Bleecker Street.

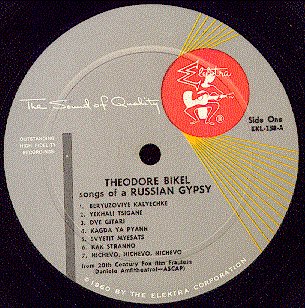

Jac met Theodore Bikel in 1955, Bikel was an actor that had come from England to the United States to

be in a Broadway play. Bikel was born in Vienna, but moved to Palestine before World War II. Bikel had

no interest in singing on records, but Jac talked him into making a record of folk songs. Jac asked him to

record the songs he knew best and he recorded a 10 inch album [EKL-32] titled Folk Songs of

Israel, which did very well. Theodore Bikel became the mainstay of Elektra from 1956 to 1961,

eventually because of his importance to the founding of Elektra, Holzman sold Bikel a 5% share of

Elektra

for $20,000 which returned a half million to Bikel when Elektra was sold.

Jac met a neighbor in his apartment building, Nina Merrick, in 1955. Jac knocked on her door and asked

to borrow some napkins. Later, he asked her out, and on their third date asked her to marry him. Nina

Holzman became the first paid employee of the Elektra Record Company.

Elektra continued to expand, and they next signed Josh White, a major folk singing star. Josh started

recording in 1931, and in the early '50s was recording for the major label Decca, when abruptly Decca

refused to record him because he had been placed on the Joe McCarthy blacklist (Joe McCarthy was a

United States Senator who built his career with Communist witch hunts in the early '50s. His

underhanded

tactics later got him censured by the Senate.). Anyone who was put on the blacklist - because of

suspected or rumored Communist leanings - found themselves unable to work because the large record

companies, radio and TV networks would not hire anyone on the blacklist. Many of the early folk singing

stars found themselves in the same situation, including Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and the Weavers.

Josh White was put on the blacklist because he refused to testify against his friend Paul Robeson. When

Decca would not record him, Holzman defied the blacklisting and signed White to Elektra and issued

several successful albums.

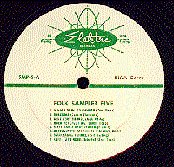

In 1956, Elektra pioneered the use of a music sampler as a way to boost record sales. Record

companies

had issued record compilations to radio stations prior to this, and even Elektra issued a 10 inch sampler

[SMP-1] to radio stations in 1954. But SMP-2 was issued for sale to the public, with a modest $1.25 price

tag. It was made up of songs by various artists in the Elektra catalog. The idea was to use a low price to

lure customers to purchase the sampler in order to interest the buyers in purchasing other records in the

Elektra catalog. Holzman introduced a provision into all of the Elektra artists' contracts that allowed the

use of a limited number of songs on sampler records without paying royalties for the use of the song.

The

artists agreed to this because it stimulated sales of their albums.

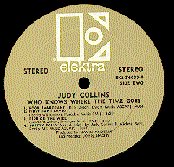

Elektra continued to expand into the early '60s with a catalog dominated by folk music. Holzman signed

one of his most important artists in 1961, when Judy Collins signed an Elektra contract. Her first album

[EKL-209], titled A Maid of Constant Sorrow, was recorded at Fine Sound Studio on 57th Street

and

sold about five thousand copies. Many critics dismissively called her a Joan Baez clone, but Holzman

immediately began work on her next album, Golden Apples of the Sun [EKL-222]. Jac Holzman

had become so involved in the day-to-day management of Elektra that he turned over production of the

Collins album to Mark Abramson. With this album and the many more Judy Collins recorded for Elektra,

she forged a distinctive style of her own and had great success for them.

After 1961, it was rare for Jac to produce an artist himself, as he turned over most of the production work

to Abramson, and later Paul Rothchild. Jac concentrated on Elektra management and the signing of new

artists. In 1962, Jac thought that New York had become stale musically, so he opened a west coast

office

on Santa Monica Boulevard and Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles. Holzman moved his family to

California.

When Jac heard the astonishing first album by Bob Dylan - and realized Elektra had missed out on

Dylan

while he was in California - he closed down the west coast office and moved back to New York. Shortly

after returning to New York, Holzman hired Paul Rothchild as a producer and gave him the Even Dozen

Jug Band to produce. The Even Dozen Jug Band, with 12 members, did not have much success for

Elektra but many of the members went on to future fame, including John Sebastian (Lovin' Spoonful),

Steve Katz (Blood, Sweat and Tears) and Maria Muldaur (top-10 hit "Midnight at the Oasis").

Elektra moved more seriously into blues music in 1963, leasing a record by three white bluesmen. The

record, titled Blues, Rags and Hollers by Koerner, Ray and Glover, was very influential. Koerner,

Ray and Glover came to New York and recorded directly for Elektra. Elektra moved into electric blues

when Paul Rothchild signed the Paul Butterfield Blues Band in 1965. Rothchild ended up recording their

first album three times before he felt he got it right. The album cost $50,000, which was a staggering

sum

for the time, but the album was brilliant and sold more copies than any other Elektra album up to that

time.

As Paul Rothchild has since said, "It made the electric blues a viable form for popular music". When Bob

Dylan wanted to perform at Newport with an electric band to back him up, he got the Butterfield Blues

Band.

In 1963 Jac came up with an idea to start a classical music label as part of Elektra, remembering back to

his college days when he wanted to buy two classical albums but could only afford one. He wanted to

make it possible for people to buy inexpensive classical records, just like you were able to buy

paperback

copies of great literature. To keep costs low, he knew that he would not be able to record the music

himself, so he flew to Europe and saw the large classical record companies in England and France. He

secured the cream of the crop of their classical music titles from their vaults for $500 per album plus a

royalty. The record companies contacted were happy to lease Jac albums that they had no chance of

ever

marketing in the United States themselves. Jac named the label Nonesuch, and Bill Harvey, the artistic

director of Elektra, came up with distinctive packaging. The slogan for the Nonesuch line was "Quality

Recordings at the Price of a Quality Paperback". Nonesuch records sold for $2.50, half the price of a

classical album by the majors. The Nonesuch label was very successful and became a money making

machine for Elektra.

Eventually, Elektra did record two of the most successful albums on Nonesuch by using one of their own

employees. Joshua Rifkin was a classically trained musician and a former member of the Even Dozen

Jug

Band who was working as an arranger for Elektra. In 1965, Jac had asked Rifkin to do an album of

classical interpretations of Lennon-McCartney songs, and the result was The Baroque Beatles

Book {Elektra EKS-7306]. The record took off, making #83 on the Billboard Album charts, and

was even played on AM radio. Later, Rifkin proposed to Jac that they do an album of Scott Joplin piano

rags for Nonesuch. Jac agreed, and the result was Piano Rags By Scott Joplin [Nonesuch 73026]

which led to a revival of ragtime in the United States, and later the use of Scott Joplin's music in the

movie

The Sting.

In 1965, Elektra had the inside track to sign the Lovin' Spoonful because of Elektra's relationship with

John Sebastian (in the Even Dozen Jug band and by using him as a session player). Paul Rothchild

lobbied Jac to pay the $10,000 being asked by the group, but Holzman thought the price was too high.

Moreover, Holtzman felt that to justify the price tag, it would force Elektra to sell top forty singles. Elektra

had never had a successful single, but Holzman finally agreed, and the $10,000 was paid to the group.

Then the Lovin' Spoonful were told that a contract they had signed for publishing rights to their songs

included a provision to record for the publishing company's record arm, Kama Sutra. Elektra felt they

had

legal claim to the Lovin' Spoonful, but Jac decided not to start a messy court battle because of his

friendship with John Sebastian.

After losing the Lovin' Spoonful, who became fabulously successful, Jac Holzman was on the lookout for

a

breakthrough pop band for Elektra. The New York groups had been picked over by the record

companies

with lots of pop experience, so in 1965 Jac Holzman headed for Los Angeles again. On the Sunset strip

Jac discovered the band Love, headed by Arthur Lee. In his autobiography, Holzman said of Love, "Five

guys of all colors, black, white and psychedelic-that was a real first. My heart skipped a beat. I had found

my band!" Elektra started a new numbering system with the first Love album [EKS-74001] and for the

first

time in Elektra history they put a single onto the charts with "My Little Red Book." In 1967, Love followed

their first album with "Forever Changes" [EKL-74013] which is incredible, an album that ranks near the

top

as one of the best albums ever made.

In May, 1966, Jac flew to Los Angeles to meet with Love, who were playing at the Whiskey-A-Go-Go.

Their opening act was a group which Arthur Lee had a high opinion of, and Lee suggested that Jac sign

them to Elektra. Jac initially was unimpressed with the group but went back several times to see them

perform. On his fourth visit, Jac realized that this was no run-of-the-mill rock band and decided to sign

them. The group was the Doors. Jac wanted Paul Rothchild to produce them, but when Rothchild flew to

L.A. to hear them, he told Holzman he was nuts for signing the group and that he (Rothchild) did not

want

to produce them. Finally, Jac told him, "Paul, I never thought I'd say this to you, but you owe me. You've

got to do this band. You are the only person for the job." Rothchild reluctantly agreed. The group was

taken to Tutti Camarata's Disney studios to record their first album, which took about a week. Elektra

issued "Break on Through (To the Other Side)" as the first single from the album, and it received modest

airplay stalling at number 106. They immediately issued the second single from the album, "Light My

Fire".

The version on the album is seven minutes long, and Jac insisted it be cut for AM play. The Doors said it

couldn't be cut, but Rothchild edited the song to about three minutes and then played it for them. They all

agreed to issue it. In June, 1967, "Light My Fire" reached the Number One position in the pop charts,

becoming Elektra's first #1 single. The album was just as successful, and in the last 30 years the Doors

have sold over 45 million records.

With the success of the Doors and Love, Elektra moved away from the small folk label image to a label

that could handle rock acts. Holzman decided to establish a west coast office again and built a state-of-

the-art studio at 962 North La Cienega Boulevard. This established a permanent west coast presence

for

Elektra, and Jac Holzman began dividing his time between New York and L.A. By the late '60s, Elektra

was having success with the Doors, Judy Collins, Tim Buckley and a group called Bread. But the record

business was changing, and Jac knew Elektra could not survive as a small independent label. He did

not

want to merge Elektra with any of the long established (bureaucratic) majors, Columbia, RCA, Decca or

Capitol. As early as 1966, he had talked with Warner Brothers about a sale, and became friends with Mo

Ostin who was running the Reprise label for Warners. In 1967, Warner Brothers had purchased Atlantic

Records, a label whose rise had paralleled Elektra. Jac talked to Mo Ostin, who had recently become

head of Warner Brothers, about combining the two companies and establishing a record distribution

arm.

Ostin went to Steve Ross, the chairman of the Warner Brothers parent company Kinney Corp. (later

called

Warner Communications), and proposed that they buy Elektra. In negotiations with Warner Brothers, Jac

Holzman asked for, and received, 10 million dollars for the company. Jac Holzman agreed to remain

with

the company for three years, with Warner Brothers having an option for two additional years.

Jac Holzman continued to run Elektra under the Warner Communications umbrella. He signed Carly

Simon, and she had a lot of success with the label. He also signed Harry Chapin to the label and was so

excited with his talent that he returned to record production for the first time in many years to do Chapin's

Heads and Tales album [Elektra EKS-75023]. By 1973, Holzman wanted to retire to a home he

built in Maui, Hawaii. When Warner Communications missed the deadline for picking up the option for

the

two additional years of service required by his contract. Holzman notified them that he was leaving the

company. Warner's tried to change his mind, but Jac Holzman retired at the age of 42 in Hawaii.

During the mid to late '70s, Elektra expanded its roster of artists from pop (Neil Sedaka, Tony Orlando &

Dawn, Sparks, the Cars, etc) to country (Eddie Rabbitt and Jerry Lee Lewis, among others), heavy rock

(Queen) and soul and funk (Patrice Rushen and Donald Byrd). Elektra also released records by

punk/new

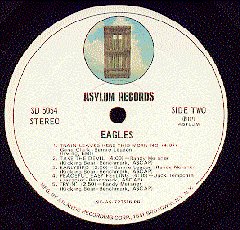

wave groups such as Television and the Dictators. Elektra Records and Asylum Records were combined in 1974.

In 1982, Elektra founded its own jazz-rock orientated subsidiary Elektra Musician, while adopting a new

consolidated numbering system, the 60000 series (which is still running today), and setting up

distribution

deals for labels such as Beserkley, Planet, Solar, and others.

Elektra continues today as part of Time-Warner Communications and is still very successful releasing

records by such different artists as Metallica, Third Eye Blind, or rapper Ol' Dirty Bastard, as well as

distributing independent English-founded labels as Mute (Depeche Mode) or Fiction (the Cure).

Jac Holzman wrote his autobiography titled Follow the Music: The Life and High Times of Elektra

Records in the Great Years of American Pop Culture (with Gavan Daws) in 1998.

This Elektra history was written using information from Follow the Music by Jac Holzman and

Gavin

Daws and The American Record Label Directory and Dating Guide, 1940-1959 by Galen Gart.

The Elektra discography covers releases by Elektra and subsidiaries Dandelion and Countryside. This

discography does not cover the Elektra classical music subsidiary Nonesuch. It was compiled using

information from Follow the Music, Schwann record catalogs from 1954 to 1982, a 1962

Phonolog,

WEA catalogs from 1982-84, and the record collections of Dave Edwards, Mike Callahan and Patrice

Eyries.

We would appreciate any additions or corrections to this discography. Just send them to us via e-mail. Both Sides Now

Publications is an information web page. We are not a catalog, nor can we provide the records listed

below. We have no association with Elektra Records. Should you be interested in acquiring

albums listed in this discography (which are all out of print), we suggest you see our Frequently Asked Questions page and follow the

instructions found there. This story and discography are copyright 2000 by Mike Callahan.

On to the Elektra Album Discography, Part 1 EKL-1 (10") Series

(1951-

1956)

On to the Elektra Album Discography, Part 1 EKL-1 (10") Series

(1951-

1956)  On to the Elektra Album Discography, Part 2 EKL-100/EKS-7100

Series

(1956-1971)

On to the Elektra Album Discography, Part 2 EKL-100/EKS-7100

Series

(1956-1971) On to the Elektra Album Discography, Part 3

EKL-4000/EKS-74000

Series (1966-1971)

On to the Elektra Album Discography, Part 3

EKL-4000/EKS-74000

Series (1966-1971) On to the Elektra Album Discography, Part 4

EKL-5000/EKS-75000

Series (1969-1974)

On to the Elektra Album Discography, Part 4

EKL-5000/EKS-75000

Series (1969-1974) On to the Asylum Album Discography, Part 1 SD-5050 Series

(1972-1973)

On to the Asylum Album Discography, Part 1 SD-5050 Series

(1972-1973)  On to the Elektra/Asylum Album Discography, Part 5 E-1000

Series (1974-1978)

On to the Elektra/Asylum Album Discography, Part 5 E-1000

Series (1974-1978) On to the Elektra/Asylum Album Discography, Part 6 6E-100

Series (1977-1981)

On to the Elektra/Asylum Album Discography, Part 6 6E-100

Series (1977-1981) On to the Elektra/Asylum Album Discography, Part 7 5E-500

Series (1978-1981)

On to the Elektra/Asylum Album Discography, Part 7 5E-500

Series (1978-1981) On to the Elektra/Asylum Album Discography, Part 8

Consolidated 60000 Series

(1982 - )

On to the Elektra/Asylum Album Discography, Part 8

Consolidated 60000 Series

(1982 - ) On to the Elektra/Asylum Album Discography, Part 9

Miscellaneous Series: EKL/EKS-9000, 9E-300, 7E-2000, 8E-6000, BB-700, CM-1, ML-800,

EUK-250, Consolidated 90000, and Special Instructional

Series

On to the Elektra/Asylum Album Discography, Part 9

Miscellaneous Series: EKL/EKS-9000, 9E-300, 7E-2000, 8E-6000, BB-700, CM-1, ML-800,

EUK-250, Consolidated 90000, and Special Instructional

Series On to the Elektra/Asylum Album Discography, Part 10 Samplers

and

Promotional Issues

On to the Elektra/Asylum Album Discography, Part 10 Samplers

and

Promotional Issues

On to the Elektra Album Discography, Part 11 Related Labels:

Countryside, Curb, Dandelion, Light, Network, Solar

On to the Elektra Album Discography, Part 11 Related Labels:

Countryside, Curb, Dandelion, Light, Network, Solar

On to the Beserkley Album Discography

On to the Beserkley Album Discography

On to the Full Moon Album Discography Full Moon/Epic, Full

Moon/Asylum, Full Moon/Warner Bros.

On to the Full Moon Album Discography Full Moon/Epic, Full

Moon/Asylum, Full Moon/Warner Bros.

On to the Planet Album Discography

On to the Planet Album Discography

Back to the Discography Listings Page

Back to the Discography Listings Page  Back to the Both Sides Now Home Page

Back to the Both Sides Now Home Page