The New York Years (1965-1973):

Bang records was started in New York in 1965, and for a time had an extremely successful string of releases. Bert Berns was the prime mover at the label, as an owner and director of operations. Berns' friends from Atlantic, Ahmet and Neshui Ertegun and Gerry Wexler helped set up the label, and the name is an acronym for the first letters of their names. Berns had been involved in making successful records for years by the time Bang was formed, either as a songwriter or as a producer. He was responsible for "Twist and Shout", "Under The Boardwalk", "Hang On Sloopy," "Brown Eyed Girl", "Piece Of My Heart", "Everybody Needs Somebody To Love," "A Little Bit Of Soap," "Push Push," and dozens of others. Berns quickly proved as adept at running his own label as he was at making hits for others.

One of the first groups Berns signed to the label was the Strangeloves. Producer Bob Feldman was directly involved in the first four chart records on the Bang label (with three different groups!), as a songwriter, artist, and producer. As one of the people around "in the beginning" at Bang, Bob was in a unique position to tell us about what it was like being in a small, but successful, record company in the mid-1960s. Also interesting is how three songwriters from New York could become the first Australian rock group to hit the US charts!

Although the Bang story starts in 1965, Feldman's success goes back several years before that, as producer and writer of the classic Angels' hits "My Boyfriend's Back," "Thank You And Goodnight," and others, with partners Jerry Goldstein and Richard Gottehrer in Feldman-Goldstein-Gottehrer (FGG) Productions. The following recollections on history of the label and the Strangeloves were recorded in an interview for Both Sides Now Stereo Newsletter in 1990:

Bob Feldman: We were writing and making demos of our songs, and we were using the Angels as singers on our demos. They told us that they had been with Caprice Records, and they weren't recording and they weren't happy, so we worked out a deal with Caprice to let them go. The night we cut "My Boyfriend's Back," we cut four A sides with four different groups, because we didn't have a lot of money [for studio time] and we put the same B-side on all four songs. One was Heavy And The Companions, we sold that master to Columbia, we sold another master to Kapp Records, we sold three of the four, one we never sold. But one of the four was "My Boyfriend's Back." The 45 had an edit where the instrumental break was taken out of it, and some splicing here and there, but the long version on the album My Boyfriend's Back [Smash SRS-67039] is the uncut song.

"My Boyfriend's Back" was banned. We had to put out the record without the intro. We had to do edits for a lot of radio stations, including MCA in New York. The followup to "My Boyfriend's Back" was supposed to be "The Guy With The Black Eye." It's on the album, you've got to listen to it. It picks up the story. The boyfriend comes back and gets the guy and beats him up for saying all these things. This is the natural followup, right? When you listen to it, it sounds like in the background they're singing "look at the gal with the black guy," not "look at the guy with the black eye." In 1963, radio just wouldn't play anything as controversial as a song about a white girl going out with a black guy. Smash wouldn't put it out because of what somebody might think was in the words, even if it wasn't really there.

But it was a time when you could be any group you wanted, a Ia Phil Spector, Darlene Love, or the Beach Nuts. We could just go out and make good records. And fun records. Snuff Garrett and I were in New York together on a rainy Saturday, and he says, "Let's go into the studio and make a record." No song, no nothing. Marty Coopersmith, who was in Jay and The Americans, showed up at the studio, and we did a record called "Don't Monkey With Tarzan" by The Pygmies. And Marty Coopersmith came out and had leopardskin bikini underwear on and ran through the studio with a Tarzan scream, and the record came out [Liberty 55624, ca. 1963]. We had nothing to do that day, it was raining, so we would just go and make records.

And early in the days of the Bang Label, the Strangeloves and Angels collaborated on a record as artists: The Beach Nuts.

"Out In The Sun (Hey-O)" [Bang 504, 7/65] was the Strangeloves and the Angels, along with a steel band. We were one of the first people to use a steel band on a rock and roll record. But during the session, we couldn't get through that we wanted than to play "The Banana Boat Song." Seems they never heard of it. After an hour and a half; somebody says, "you know, 'Day-O'." They say, "Day-O? Why didn't you say so?" An hour and a half, we couldn't get "The Banana Boat Song" on record. Crazy times; fun times.

Bang got started after Bert Berns did a lot of producing for Atlantic Records, a lot of the Drifters things, and other hits [not on Atlantic] like "Twist And Shout" on Wand. He was very close to Jerry Wexler and the Erteguns, and they gave him his own label to work with, which Atlantic distributed. The label name, "Bang," is actually the first initials of the four of them (Bert Berns, Ahmet Ertegun, Neshui Ertegun, and Gerald Wexler). He was personally involved with a lot of things with the label. I can't remember if he was actually in the booth when we put our voices on "I Want Candy," but he was personally involved with all the acts he signed to the label.

In 1964, we [FGG Productions] had basically cut "Bo Diddley" in Atlantic Recording Studios. We were looking to sell the master, and Atlantic loved it. They told us that they were starting a new label with Bert Berns. We had cut the track, they had loved the track, and we were going to do "Bo Diddley." But Bert Berns told us, "Why do Bo Diddley? Let's write a new song." That's how "I Want Candy" came about.

What happened was, we had a record out on Swan as the Strangeloves ["Love Love (That's All I Want

From You)", Swan 4192] before the Bang record. It hit the charts [Billboard #122, 12/19/64]. This was in

'64, just after the British Invasion hit. The West Coast was another world, but the East Coast writers and

producers were having a tough time selling anything because all anybody wanted were English groups.

We had a track lying around, and I convinced my partners that the only way we were going to get say

product was if we were British. Being that everybody was from England, we came up with the "fact" that

we were from Australia, so we became in essence the first Australian rock group to come to the United

States. We had this old track lying around that we were going to do with the Angels, but we had never

put out. The record was called "Love Love." On the back of "Love Love" was a demo of a song called

"I'm On Fire," which Jerry Lee Lewis ultimately recorded [Smash 1886, charted 4/64, #98], and it's in the

Great Balls Of Fire movie. But that was the original demo that we had cut to send to him.

Somewhere in the record I went (uses British accent) "a little love that slowly grows and grows," and did

this monologue with an accent.

What happened was, we had a record out on Swan as the Strangeloves ["Love Love (That's All I Want

From You)", Swan 4192] before the Bang record. It hit the charts [Billboard #122, 12/19/64]. This was in

'64, just after the British Invasion hit. The West Coast was another world, but the East Coast writers and

producers were having a tough time selling anything because all anybody wanted were English groups.

We had a track lying around, and I convinced my partners that the only way we were going to get say

product was if we were British. Being that everybody was from England, we came up with the "fact" that

we were from Australia, so we became in essence the first Australian rock group to come to the United

States. We had this old track lying around that we were going to do with the Angels, but we had never

put out. The record was called "Love Love." On the back of "Love Love" was a demo of a song called

"I'm On Fire," which Jerry Lee Lewis ultimately recorded [Smash 1886, charted 4/64, #98], and it's in the

Great Balls Of Fire movie. But that was the original demo that we had cut to send to him.

Somewhere in the record I went (uses British accent) "a little love that slowly grows and grows," and did

this monologue with an accent.

So we sold the record to Swan and said that we were from Australia. And they bought it. So we had a record that hit the charts on Swan, but they wouldn't pay for a followup record. So we went into the studio with our own money, and cut "I Want Candy."

Following up with the idea of being an Australian group, the three billed themselves as the Strange Brothers, Miles, Niles, and Giles, and started touring.

I put on a wig, long hair and a beard. We invented Armstrong, Australia, and said that the reason we looked different was that we had the same mother, but three different fathers, and that I was the boomerang champion of Australia.

For our first show, we went to The Dome in Virginia Beach, and we were co-headlining with Chuck Berry. Gene Pitney was on the show, and the Shangri-Las, and a bunch of people. We drove two cars down to Newport News [an adjacent city], then got on a private jet that taxied to Virginia Beach. It never left the ground; it was like a couple of miles. There were 3000 people with banners waiting, the mayor with the keys to the city, television cameras, signs saying "Welcome to America, Strangeloves." And instead of flying in from Australia, we had driven all night from New York to get there.

On a TV show, I think it was KDKA in Pittsburgh, a guy, I think his name was Clark Race, surprised me and handed me a boomerang. I had never seen one in my life. He asked me to demonstrate my championship technique. I threw the damned thing, and they had one camera shooting, and I hit the cameraman, and the camera fell over. So he says to me, "that's not the way you hold a boomerang." I said, "That's why I'm the champion and you're not." It was just marvelous.

We did this for a year, we toured with every major British act, the Beach Boys thought we were insane, so we did three tours with the Beach Boys. They thought we were nuts, and we thought they were nuts.

"I Want Candy" was also banned! It went to #1 in St. Louis and they never played it. Crazy times.

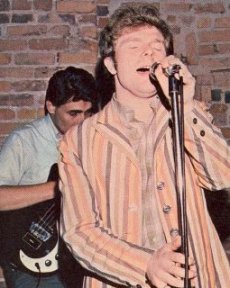

We were doing a show in Tulsa, Oklahoma, with the Dave Clark Five. "Hang On Sloopy" was originally on the Strangeloves album, the same track "Hang On Sloopy" was supposed to be the followup to "I Want Candy." The Dave Clark Five were leaving, getting ready to go back to England, and they needed a new single. They loved what we were doing with "Sloopy." They taped it. We were supposed to fly home, and there were tornados all over the place, all over that part of the country, and I didn't want to fly in that, so I said, "No, we're driving." So an agent said, "Listen, if you're driving home, why don't you stop in Dayton, Ohio, and do a show on the way home and pick up a couple of thousand bucks?" We said fine.

I

remember it was Friday night, we stopped in Dayton, and Rick and The Raiders were a substitute

backup band. They were a last minute replacement as a backup for the Strangeloves. We were standing

in the wings watching them, and I heard a sixteen year-old [Rick Zehringer, later Derringer] that played

guitar like I'd never heard anybody play a guitar. And they backed us up. We were worried about the

Dave Clark Five, because they had told us that they were going to cut "Hang On Sloopy." Being that "I

Want Candy" was just out and on the way up, there was no way we were going to get it out [before they

did without killing "Candy"]. We heard the group who would be the McCoys, we thought they'd be great,

had them call their folks, and we all drove to New York. We named them on the way, from Dayton to

New York. First it was the Real McCoys, then just the McCoys. We got there, went right in the studio, put

their voices on the track, and then put Rick's guitar on it. But if you listen to the Strangeloves version of

"Hang On Sloopy," listen to the track, it's the same. The McCoys single also has an edit, there was an

extra verse we took out, strictly because the song was too long for a single. Bert Berns was a stickler for

getting airplay, and at that time songs being under three minutes was necessary.

I

remember it was Friday night, we stopped in Dayton, and Rick and The Raiders were a substitute

backup band. They were a last minute replacement as a backup for the Strangeloves. We were standing

in the wings watching them, and I heard a sixteen year-old [Rick Zehringer, later Derringer] that played

guitar like I'd never heard anybody play a guitar. And they backed us up. We were worried about the

Dave Clark Five, because they had told us that they were going to cut "Hang On Sloopy." Being that "I

Want Candy" was just out and on the way up, there was no way we were going to get it out [before they

did without killing "Candy"]. We heard the group who would be the McCoys, we thought they'd be great,

had them call their folks, and we all drove to New York. We named them on the way, from Dayton to

New York. First it was the Real McCoys, then just the McCoys. We got there, went right in the studio, put

their voices on the track, and then put Rick's guitar on it. But if you listen to the Strangeloves version of

"Hang On Sloopy," listen to the track, it's the same. The McCoys single also has an edit, there was an

extra verse we took out, strictly because the song was too long for a single. Bert Berns was a stickler for

getting airplay, and at that time songs being under three minutes was necessary.

The liner notes for The Strangeloves album were written with tongue firmly in cheek, leaving plenty of clues that the group was actually Feldman, Goldstein, and Gottshrer. It would seem just a matter of time before someone uncovered them...

Nobody uncovered us. We went out on a tour with the McCoys, the McCoys were the Strangeloves' backup band, and it was the Stangeloves-McCoys, but halfway through the tour, "Hang On Sloopy" became #1, and they became the ultimate stars of the show. I remember I took off my fall, it was my wife's hairpiece, and they booed me. They didn't want to know that it wasn't real. They wanted to believe that we were from Australia. Later, Max's Kansas City and New York had all our records in the juke box saying we were the fathers of Punk Rock, because we dressed in zebra skins, leather pants, carried spears, and did all sorts of wierd things.

One of the things that has puzzled record collectors is what came out in stereo on Bang. For example, the first album, by the Strangeloves, is listed as being stereo in some of the references from 1965 and 1966, and the album pasteover has a stereo banner on it, but nobody's ever found one in stereo.

There wasn't really a hell of a lot of stereo on the early Bang that I can remember. The Strangeloves I don't remember doing a stereo on. We mixed it to mono. We did it actually as a two-track, I think. I don't remember doing a stereo. If it was, it was a phony stereo. As for someone finding a stereo copy, if I didn't do one, they couldn't find one. Most of what we did was recorded on four track or eight track, but it was mixed down to mono. You have to remember that AM radio was king. As for FM stereo, there really wasn't that much of a call then. That didn't really start happening until the end of 1966, or 1967.

The last Bang record we had anything to do with was the McCoys' "Beat The Clock," in late 1966. That's a long time ago.

And after the Strangeloves?

I have one of the all-time oldies on KDKA. I was part of a duet called Rome And Paris, Jerry Goldstein and I tried to imitate the Flamingos. We did "Because Of You" [Roulette 4681, 7/66 Billboard # 104]. I did sing on a couple of records besides that, but I don't remember them offhand, they weren't too memorable.

The Strangeloves had one other chart hit, "Honey Do," [Sire 4102, #120] in late 1968. Today, the three former Strangeloves are alive and well, although scattered throughout heir "adopted" country, the US. Jerry Goldstein is on the west coast and Richard Gottehrer is on the east coast, both still in the music business, while Bob Feldman makes Colorado his home. The McCoys moved to Mercury Records in 1967, went through numerous (and essentially total) personnel changes through the early 1970s, and eventually became a country and western bar band bearing no resemblance whatever to Rick and The Raiders. Rick Derringer, at that time long since departed from the McCoys, had several solo singles chart in the mid-1970s, most notably "Rock And Roll Hoochie Coo" [Billboard #23] in early 1974.

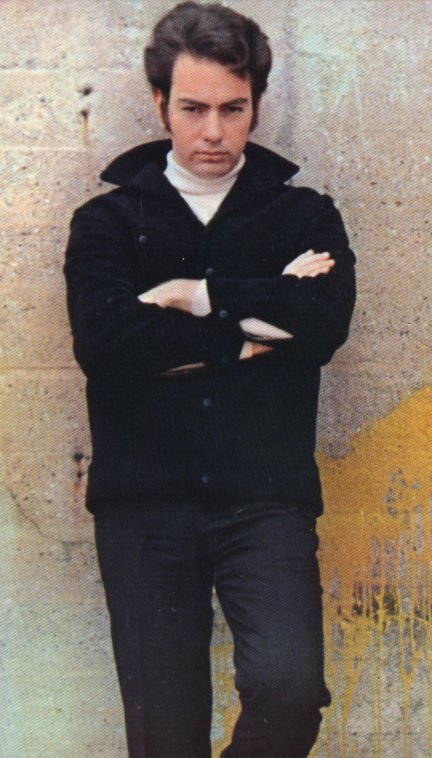

In addition to FGG, who produced the first three albums for Bang (The Strangeloves and

McCoys albums), Berns used other producers, such as Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich, who were Neil

Diamond's producers. Diamond was a New Yorker who had been trying to break into the music business

since he was a teenager, when he recorded an obscure single for the Duet label in 1960. He worked as

a songwriter in new York in the early 1960s, where he undoubtedly met fellow Tin Pan Alley songwriters

Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich. After another obscure single in 1963 ["Clown Town"/"At Night" on

Columbia 42809] and a songwriting success in 1965 ["Sunday and Me" for Jay and the Americans], he

hooked up again with Barry and Greenwich as producers and signed with Bang Records. The three were

considering which of Diamond's songs to record for a single when Barry and Greenwich heard "Solitary

Man," a song Diamond wrote about his social life, a personal song he joked that he used just for

self-torture. They convinced him to record it and issue it as his first Bang single [Bang 215]. Although it

only reached #55 nationally, it was a moderate hit in some of the major markets like New York and

Chicago, and got him some recognition. His second single, "Cherry Cherry" [Bang 528], though, reached

top-10 nationally and established him as a recording star. The refrain "She's got the way to move me..."

was widely misinterpreted as "She's got the wedding movement...," which, although somewhat

nonsensical, was thought to be kind of quaint and inventive, and added to the public's like of the song.

In addition to FGG, who produced the first three albums for Bang (The Strangeloves and

McCoys albums), Berns used other producers, such as Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich, who were Neil

Diamond's producers. Diamond was a New Yorker who had been trying to break into the music business

since he was a teenager, when he recorded an obscure single for the Duet label in 1960. He worked as

a songwriter in new York in the early 1960s, where he undoubtedly met fellow Tin Pan Alley songwriters

Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich. After another obscure single in 1963 ["Clown Town"/"At Night" on

Columbia 42809] and a songwriting success in 1965 ["Sunday and Me" for Jay and the Americans], he

hooked up again with Barry and Greenwich as producers and signed with Bang Records. The three were

considering which of Diamond's songs to record for a single when Barry and Greenwich heard "Solitary

Man," a song Diamond wrote about his social life, a personal song he joked that he used just for

self-torture. They convinced him to record it and issue it as his first Bang single [Bang 215]. Although it

only reached #55 nationally, it was a moderate hit in some of the major markets like New York and

Chicago, and got him some recognition. His second single, "Cherry Cherry" [Bang 528], though, reached

top-10 nationally and established him as a recording star. The refrain "She's got the way to move me..."

was widely misinterpreted as "She's got the wedding movement...," which, although somewhat

nonsensical, was thought to be kind of quaint and inventive, and added to the public's like of the song.

Diamond's first album was released hot on the heels of "Cherry Cherry's" success. Called The Feel of Neil Diamond, it was set up as a look into the studio life at the time. A memo on the back of the cover by Bert Berns told of things that allegedly happened during recording of the album, and the recordings themselves had studio talk at times with Barry and Greenwich encouraging (demanding?) Diamond as he prepared to sing. In addition to his own material, he made it through some other hits, sometimes seriously and sometimes not. "La Bamba," in particular, has confused anyone who knows the actual Spanish words (huh? what is Diamond singing?), since it sounds like they were taken phonetically off the Ritchie Valens single.

More hits followed ["I Got The Feelin' (Oh No No)," Bang 536, #16; "You Got To Me," Bang 540, #18; "Girl, You'll Be A Woman Soon," Bang 542, #10; "Thank The Lord For The Night Time," Bang 547, #13; and "Kentucky Woman," Bang 551, #22]. A second album, Just for You, was issued in the summer of 1967, about the time "Thank the Lord for the Night Time" was current. By the time "Kentucky Woman" was a hit, however, Diamond's contract was running out and he opted to go with the Uni label. Bang issued a Greatest Hits album, but that was it. Bang issued several more singles from Diamond's back catalog, and most of them were charters due to his growing popularity. These included "New Orleans" [Bang 554,#51, from his first LP], "Red Red Wine" [Bang 556, #62, from his second LP], "Shilo" [Bang 575, #24, from his second LP], "Solitary Man" [Bang 578, #21, a reissue of Bang 215 that did far better the second time around], "Do It" [Bang 580, #36, the flip of the original release of "Solitary Man"], "I'm A Believer" [Bang 586, #51, from his second LP], and "The Long Way Home" [Bang 703, #91, from his second LP].

To say that Bang shamelessly exploited his material following his departure (in a tried-and-true record company manner) is perhaps a bit overstated; after all, the public bought them eagerly. (Well, maybe the issuing of the Shilo and Do It albums, with all recycled songs, was a bit much...) Eventually, Diamond himself put a stop to the reissues by buying the masters back. He now controls the CD reissue of his Bang catalog, and for the most part, his preference is to reissue the songs in mono.

Diamond's Bang songs have some variations, with three different versions of "Solitary Man," and two versions each of "Do It; 'Shilo," and 'i'm A Believer." The original 45 versions of "Solitary Man" and "Do It" have never appeared In stereo; the alternate versions are different takes or have added instrurnentation. The discography notes the different versions.

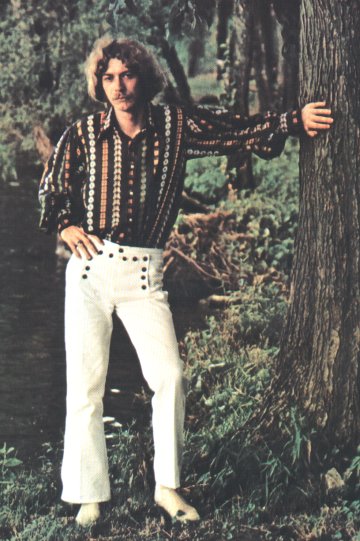

Another hitmaker for Bang was Van Morrison, the singer from Belfast, Ireland, who had

gone back to Ireland after leaving his group, Them. Bert Berns brought him to New York and produced

an album for Morrison, Blowin' Your Mind, and from those sessions, Bang eventually issued three

separate albums! The big hit single, "Brown Eyed Girl" [Bang 545] reached the top-10, but it was the

only hit from the Bert Berns sessions. Released in the summer of 1967, it was indeed strange times in

radioland, as "Brown Eyed Girl" ran into censorship problems due to the line, "makin' love in the green

grass behind the stadium." Berns quickly provided a "cleaned-up version," splicing in a line from another

part of the song, the result being, "Laughin' and a-runnin', behind the stadium." This version was used

for the mono version of the album, and appears from time to time on reissues.

Another hitmaker for Bang was Van Morrison, the singer from Belfast, Ireland, who had

gone back to Ireland after leaving his group, Them. Bert Berns brought him to New York and produced

an album for Morrison, Blowin' Your Mind, and from those sessions, Bang eventually issued three

separate albums! The big hit single, "Brown Eyed Girl" [Bang 545] reached the top-10, but it was the

only hit from the Bert Berns sessions. Released in the summer of 1967, it was indeed strange times in

radioland, as "Brown Eyed Girl" ran into censorship problems due to the line, "makin' love in the green

grass behind the stadium." Berns quickly provided a "cleaned-up version," splicing in a line from another

part of the song, the result being, "Laughin' and a-runnin', behind the stadium." This version was used

for the mono version of the album, and appears from time to time on reissues.

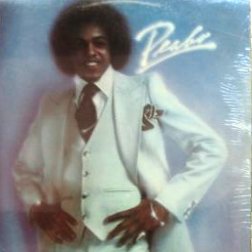

On December 30, 1967, Bert Berns died at the age of 38, and his wife Ilene took over the company. It

was on her watch that the endless reissuing of the back catalogs of Neil Diamond and Van Morrison

took place, but it was also on her watch that she found the star for Bang's future, Paul Davis. A

singer/songwriter from Mississippi, Davis had fronted a group called the Reivers in the 1960s, and even

had a single released on the White Whale label. He signed with Bang in 1969, and Ilene Berns shipped

him to New York to work with Barry and Greenwich to learn about producing. Eventually, Davis had hits

for Bang from 1970 to 1980. He then went on to a further career as a country music songwriter and

sometimes artist for Arista.

On December 30, 1967, Bert Berns died at the age of 38, and his wife Ilene took over the company. It

was on her watch that the endless reissuing of the back catalogs of Neil Diamond and Van Morrison

took place, but it was also on her watch that she found the star for Bang's future, Paul Davis. A

singer/songwriter from Mississippi, Davis had fronted a group called the Reivers in the 1960s, and even

had a single released on the White Whale label. He signed with Bang in 1969, and Ilene Berns shipped

him to New York to work with Barry and Greenwich to learn about producing. Eventually, Davis had hits

for Bang from 1970 to 1980. He then went on to a further career as a country music songwriter and

sometimes artist for Arista.

Davis started with the non-charting single "Mississippi River"/"If I Wuz A Magician" [Bang 568] in 1969. When that failed, he switched to the Bert Berns-penned "A Little Bit of Soap," which had been a top-15 hit for the Jarmels in 1961 [Laurie 3091]. It also had been done by the Exciters in 1966, during their days with Bang [Bang 515, #58]. Davis did a bit better with it, making #52 in 1970 [Bang 576], demonstrating that at least the song had staying power. Davis' followup, "I Just Wanna Keep It Together," did about the same at #51 [Bang 579]. Davis then dropped off the charts for more than two years until "Boogie Woogie Man" made #68 in early 1973. An album released to follow up on the single didn't sell well.

The Atlanta Years:

The label moved to Atlanta in 1973, opting for one last Van Morrison reissue on the way. Actually,

T.B. Sheets was not a reissue in the strict sense, but an album of outtakes and alternates from

the Blowin' Your Mind session. As such, it was at least interesting to Van Morrison's fans.

The label moved to Atlanta in 1973, opting for one last Van Morrison reissue on the way. Actually,

T.B. Sheets was not a reissue in the strict sense, but an album of outtakes and alternates from

the Blowin' Your Mind session. As such, it was at least interesting to Van Morrison's fans.

Paul Davis' next single, "Ride 'Em Cowboy" [Bang 712, #23], was a tear-jerker about a aging rodeo bronc rider. It was his biggest hit yet, and portended his move into country music. It wasn't until "I Go Crazy" in 1977 [Bang 733], though, that he finally reached the top 10. The song seemed to hang around forever on the charts, lasting an astonishing 40 weeks, at that time setting the chart record for longevity. He had two more top-30 hits for Bang with "Sweet Life" [Bang 738, #17] and "Do Right" [Bang 4808, #23] before moving to Arista in 1981.

Besides Paul Davis, Bang had one other major hitmaking act during its days in Atlanta: a funky soul group called Brick. Brick hit the scene with "Dazz" ("dazz, dazz, disco jazz") in 1976, and followed over the years with six albums that made the charts for Bang. Other than Paul Davis and Brick, and Elton John's band member Nigel Olsson, the label had a few scattered one-and-done albums, including a comedy album by New York deejay Don Imus. The label was sold to CBS in 1982.

Shout Records and Bullet Records were Bang subsidiaries.

We would appreciate any additions or corrections to this discography. Just send them to us via e-mail. Both Sides Now Publications is an information web page. We are not a catalog, nor can we provide the records listed below. We have no association with Bang Records, Shout Records, Bullet Records, or Sony Music. Should you be interested in acquiring albums listed in this discography (which are all out of print), we suggest you see our Frequently Asked Questions page and follow the instructions found there. This story and discography are copyright 1990, 2003 by Mike Callahan.

The Bang Records Story

The Bang Records Story