The Vee-Jay Story

The Vee-Jay Story Vee-Jay Records. In cold, hard facts, Vee-Jay

was founded in Gary, Indiana in 1953 by Vivian Carter and James C. Bracken (later that year, Mr. & Mrs.

Bracken), who used their first initials for the label's name. The first song they ever recorded made it to

the top ten of the national rhythm & blues charts. In a short time, Vee-Jay was the most successful

black- owned record company in the United States. By 1963, they were charting records faster than

some of the major labels. They were the first U.S. company to have the Beatles. In one month alone in

early 1964, they sold 2.6 million Beatles singles. Two years later, the company was bankrupt.

Vee-Jay Records. In cold, hard facts, Vee-Jay

was founded in Gary, Indiana in 1953 by Vivian Carter and James C. Bracken (later that year, Mr. & Mrs.

Bracken), who used their first initials for the label's name. The first song they ever recorded made it to

the top ten of the national rhythm & blues charts. In a short time, Vee-Jay was the most successful

black- owned record company in the United States. By 1963, they were charting records faster than

some of the major labels. They were the first U.S. company to have the Beatles. In one month alone in

early 1964, they sold 2.6 million Beatles singles. Two years later, the company was bankrupt.

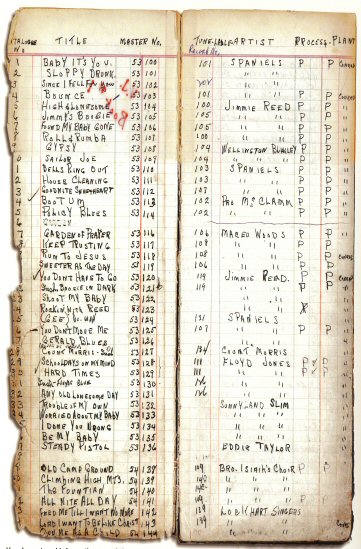

The Spaniels at that time consisted of lead singer James "Pookie" Hudson and four of his classmates. It

was on May 5, 1953, that the group recorded the four tunes that launched the label: "Baby It's You, "

"Sloppy Drunk, " "Since I Fell for You" and "Bounce. " They were backed by a small Red Saunders contingent.

The Spaniels at that time consisted of lead singer James "Pookie" Hudson and four of his classmates. It

was on May 5, 1953, that the group recorded the four tunes that launched the label: "Baby It's You, "

"Sloppy Drunk, " "Since I Fell for You" and "Bounce. " They were backed by a small Red Saunders contingent.

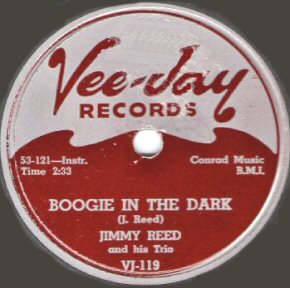

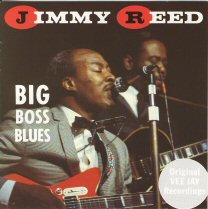

Calvin Carter: "When we first met Jimmy Reed in 1953, he was actually working in Chicago in

the stockyards, where he was cutting up cattle. He was playing harmonica for a guy called King David

that we were interested in. So we were having a rehearsal with them one day and we heard Jimmy play.

We asked him, 'Do you have any songs that you've written?' And he says, 'No, but I've got some I made

up.' And that was how we got Jimmy Reed."

Calvin Carter: "When we first met Jimmy Reed in 1953, he was actually working in Chicago in

the stockyards, where he was cutting up cattle. He was playing harmonica for a guy called King David

that we were interested in. So we were having a rehearsal with them one day and we heard Jimmy play.

We asked him, 'Do you have any songs that you've written?' And he says, 'No, but I've got some I made

up.' And that was how we got Jimmy Reed."

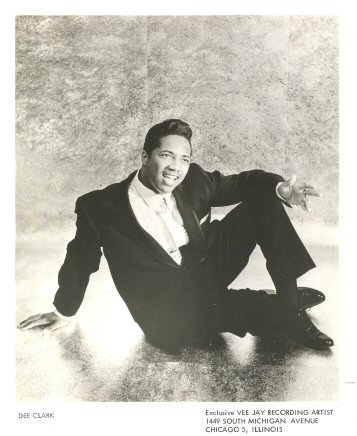

Jerry Butler: There's a man by the name of Calvin Carter. He did A&R for Vee Jay records, a

company man. His job was to go out and cut hits. Today he would be called a promoter. Calvin did it for

12 years, and when you list the acts he signed, using no other ears to depend on but his own, it reads

like a 'who's who' in the music business. He covered every base. For example, gospel acts he signed:

Five Blind Boys, the Staple Singers, the Swan Silvertones, Maceo Woods, the Raspberry Singers. In the

blues field, he signed Jimmy Reed and John Lee Hooker. In R&B, the Dells, the Spaniels, myself, the El

Dorados. Female singers such as Priscilla Bowman and Betty Everett. The jazz artists included Eddie

Harris and the MJT+3.... Unfortunately, the only industry people knowing him today are those who came

in contact with him back in those days; but I think he deserves a place in R&B music on the same level

as Phil Spector."

Jerry Butler: There's a man by the name of Calvin Carter. He did A&R for Vee Jay records, a

company man. His job was to go out and cut hits. Today he would be called a promoter. Calvin did it for

12 years, and when you list the acts he signed, using no other ears to depend on but his own, it reads

like a 'who's who' in the music business. He covered every base. For example, gospel acts he signed:

Five Blind Boys, the Staple Singers, the Swan Silvertones, Maceo Woods, the Raspberry Singers. In the

blues field, he signed Jimmy Reed and John Lee Hooker. In R&B, the Dells, the Spaniels, myself, the El

Dorados. Female singers such as Priscilla Bowman and Betty Everett. The jazz artists included Eddie

Harris and the MJT+3.... Unfortunately, the only industry people knowing him today are those who came

in contact with him back in those days; but I think he deserves a place in R&B music on the same level

as Phil Spector."

Sid McCoy: "Even before I started A&R-ing things for Vee Jay, I used to go down to Universal

and just sit there, sit in on the sessions because they were really so fabulous. Calvin did the recording

sessions with Jimmy Reed, which were always a gas. There was first of all the music that came out, and

then there was the color. Jimmy Reed would sit there on a drum case, with the mike adjusted to it. Next

to him would be his wife, Mama Reed, and Mama Reed would have to speak the lyric to him. He'd say

'Speak the lyric to me, Mama Reed!' And they would be things that he had composed himself, in many

instances. She would be there to lay it on him phrase by phrase as he went through it. Just

fantastic."

Sid McCoy: "Even before I started A&R-ing things for Vee Jay, I used to go down to Universal

and just sit there, sit in on the sessions because they were really so fabulous. Calvin did the recording

sessions with Jimmy Reed, which were always a gas. There was first of all the music that came out, and

then there was the color. Jimmy Reed would sit there on a drum case, with the mike adjusted to it. Next

to him would be his wife, Mama Reed, and Mama Reed would have to speak the lyric to him. He'd say

'Speak the lyric to me, Mama Reed!' And they would be things that he had composed himself, in many

instances. She would be there to lay it on him phrase by phrase as he went through it. Just

fantastic."

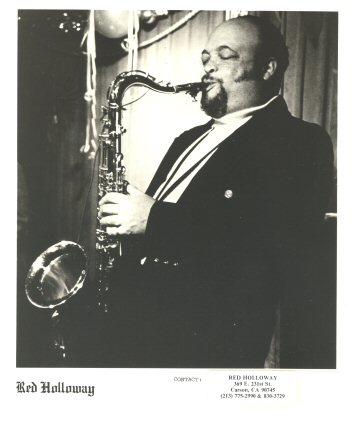

Red Holloway: "We were all with Chance Recording Company at the

time. Ewart Abner, Al

Smith, Lefty Bates, and myself. Vee Jay was just getting started, and they were in a garage on 47th

Street in Chicago. They had something going with Jimmy Reed and the Spaniels, and looking back, I

believe that 'Goodnite Sweetheart' really put them on the map. Vee Jay didn't have any money, really,

but we'd do recording sessions for them. At that time they were paying $41.25, and you might have to

wait a couple of months before you got that. So at that time Lefty, Al, and I were all working for both

Chance and Vee Jay. The people at Chance and Vee Jay were all friends at the time, so you go along

and try to help people out, because if they made it, it would mean that you would have some work. So

we never refused, because we all needed money, and they were on the same basis as we were: poor

and broke. We all had that in common. So we'd just record for them and get five dollars today, ten

dollars the next day, and whatever. They were just down-to-earth people trying to make a living."

Red Holloway: "We were all with Chance Recording Company at the

time. Ewart Abner, Al

Smith, Lefty Bates, and myself. Vee Jay was just getting started, and they were in a garage on 47th

Street in Chicago. They had something going with Jimmy Reed and the Spaniels, and looking back, I

believe that 'Goodnite Sweetheart' really put them on the map. Vee Jay didn't have any money, really,

but we'd do recording sessions for them. At that time they were paying $41.25, and you might have to

wait a couple of months before you got that. So at that time Lefty, Al, and I were all working for both

Chance and Vee Jay. The people at Chance and Vee Jay were all friends at the time, so you go along

and try to help people out, because if they made it, it would mean that you would have some work. So

we never refused, because we all needed money, and they were on the same basis as we were: poor

and broke. We all had that in common. So we'd just record for them and get five dollars today, ten

dollars the next day, and whatever. They were just down-to-earth people trying to make a living."

The El Dorados also came to Vee-Jay in 1954:

The El Dorados also came to Vee-Jay in 1954:

Betty Chiappetta: "In 1955, they also started recording Eddie Taylor, who of course never

became the big artist that he should have been. They started recording Eddie as an individual artist, but

he had been backing up Jimmy Reed on almost all his sessions."

Betty Chiappetta: "In 1955, they also started recording Eddie Taylor, who of course never

became the big artist that he should have been. They started recording Eddie as an individual artist, but

he had been backing up Jimmy Reed on almost all his sessions."

New groups to the label in 1955 included the Kool Gents and the Dells:

New groups to the label in 1955 included the Kool Gents and the Dells:

MC: The Anita Kerr Singers on R&B records? Far out.

MC: The Anita Kerr Singers on R&B records? Far out.

Calvin Carter: "I sang with the Spaniels for a short time. One of the kids was like sixteen years

old, and he couldn't go out on the road, because he was still in high school. So I took his place until

summer vacation, and then he came out. It was just a temporary thing for a few months."

Calvin Carter: "I sang with the Spaniels for a short time. One of the kids was like sixteen years

old, and he couldn't go out on the road, because he was still in high school. So I took his place until

summer vacation, and then he came out. It was just a temporary thing for a few months."

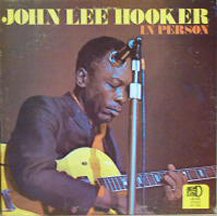

Calvin Carter: "We got John Lee Hooker out of Detroit. He was a guy who never rhymed, you

know, he just didn't have the usual rhyme lines. We only did one take on everything he did; he'd never

do it the same way twice. Of course you know he couldn't read music, but nobody could play with him

either. His timing was off, he could only play by himself. So I put some plywood on the studio floor, on

the tile floor, and that would be his drums. I just used him on guitar. Sometimes I would

use Eddie Taylor, the backup player for Jimmy Reed, on some of John Lee Hooker's things that had a

Jimmy Reed feel in the background music."

Calvin Carter: "We got John Lee Hooker out of Detroit. He was a guy who never rhymed, you

know, he just didn't have the usual rhyme lines. We only did one take on everything he did; he'd never

do it the same way twice. Of course you know he couldn't read music, but nobody could play with him

either. His timing was off, he could only play by himself. So I put some plywood on the studio floor, on

the tile floor, and that would be his drums. I just used him on guitar. Sometimes I would

use Eddie Taylor, the backup player for Jimmy Reed, on some of John Lee Hooker's things that had a

Jimmy Reed feel in the background music."

For the first time, however, all of Vee Jay's chart hits also made the pop charts. This success prompted

Vee-Jay to enter the LP market. They had initially released an album that didn't have the Vee-Jay name

on it as VJLP-100, but the first "official" album was #101.

For the first time, however, all of Vee Jay's chart hits also made the pop charts. This success prompted

Vee-Jay to enter the LP market. They had initially released an album that didn't have the Vee-Jay name

on it as VJLP-100, but the first "official" album was #101.

The Magnificents, pictured at left, late 1956: Top row (l to r): Johnny Keyes, Fred Rakestraw; Middle:

Barbara Arrington; bottom row: L.C. Cooke, Willie Myles. Cooke was Sam Cooke's brother, and writer of

Sam's first big pop hit, "You Send Me." Keyes and Cooke backed Bo Diddley on several of his hits, and

Keyes later wrote "Too Weak to Fight," which sold a million for Clarence Carter in 1970.

The Magnificents, pictured at left, late 1956: Top row (l to r): Johnny Keyes, Fred Rakestraw; Middle:

Barbara Arrington; bottom row: L.C. Cooke, Willie Myles. Cooke was Sam Cooke's brother, and writer of

Sam's first big pop hit, "You Send Me." Keyes and Cooke backed Bo Diddley on several of his hits, and

Keyes later wrote "Too Weak to Fight," which sold a million for Clarence Carter in 1970.

In addition to the El Dorados album, Vee Jay in 1957 issued the Spaniels' first album (VJLP-1002) and

"We Bring You Love" by Sarah McLawler and Richard Otto (VJLP/SR-1003). The latter was a significant

album from two points of view. First it was Vee Jay's first album venture into "pop" music, and second, it

was their first stereo album. Since stereo on disc was only invented and demonstrated in late 1957, it

showed a very innovative attitude on the part of Vee Jay to be recording in stereo this early.

In addition to the El Dorados album, Vee Jay in 1957 issued the Spaniels' first album (VJLP-1002) and

"We Bring You Love" by Sarah McLawler and Richard Otto (VJLP/SR-1003). The latter was a significant

album from two points of view. First it was Vee Jay's first album venture into "pop" music, and second, it

was their first stereo album. Since stereo on disc was only invented and demonstrated in late 1957, it

showed a very innovative attitude on the part of Vee Jay to be recording in stereo this early.

We would appreciate any additions or corrections to this story. Just send them to us via e-mail. Both Sides Now Publications is an information web page. We are not a catalog, nor can we provide the records mentioned above. We have no association with Vee-Jay Records, which is currently inactive. Should you be interested in acquiring Vee-Jay products (which are all out of print), we suggest you see our Frequently Asked Questions page and Follow the instructions found there. This story and discography are copyright 1981, 1993, 1997, 1999, 2006 by Mike Callahan. All rights reserved.

Back to the Vee-Jay Main Page

Back to the Vee-Jay Main Page  On to The Vee-Jay Story, Page 2

On to The Vee-Jay Story, Page 2  Back to the Discography Listings Page

Back to the Discography Listings Page  Back to the Both Sides Now Home Page

Back to the Both Sides Now Home Page