It was also about that time that Vee Jay welcomed newcomer Wade Flemons, who hit with "Here I

Stand":

It was also about that time that Vee Jay welcomed newcomer Wade Flemons, who hit with "Here I

Stand":

Calvin Carter: "Wade Flemons was in a group called The Newcomers, and they were from

Witchita, Kansas. We decided to use Wade as a solo singer and forget the group."

Dee Clark, who had been recording under his own name for some time on Falcon/Abner, finally caught

fire in 1958 with "Nobody But You."

Calvin Carter: "When Little Richard quit singing and went into gospel, there was a guy called

Sullivan out in California who had booked like thirty dates on Little Richard and his band, the Upsetters.

When Little Richard quit, he left him with all these dates hanging. Previously, I had put out a record by

Dee Clark where he was sounding like everybody; he could sound like Sam Cooke, Little Richard,

whoever, so Sullivan called me up and said he wanted Dee Clark to come out and sing with the

Upsetters so he could fill the Little Richard dates. That's how that came about. Dee went to the Apollo

with the Upsetters, and there he heard the Drifters. They had a western song, and Dee took the song

and changed the lyrics and made it ‘Nobody But You.' "

Sid McCoy, a longtime friend of many of the Vee Jay people finally joined the label formally in 1958 as

A&R head of the newly-formed Jazz Department.

Sid McCoy: "It was quite a while after the label started that I joined. In the meantime, I

continued in radio. A considerable period later, I came in and started A&R-ing the jazz stuff. The first

record date was a Bennie Green thing, and on it was Gene Ammons, Nat Adderly, and Tommy Flanagan

(Swingin'est, VJLP/SR-1005). We started off recording the jazz things in stereo; it became

apparent early on that the stuff should be done in stereo, because it was the state of the art."

At this time, Vee Jay was also involved with The Sutherland Lounge, a large room in Chicago's

Sutherland Hotel which featured jazz musicians regularly. One of the acts to play the Sutherland was

Miles Davis, and Vee Jay ended up with recording contrads for many of Davis' sidemen, such as Paul

Chambers, Wynton Kelly, Wayne Shorter, Frank Strozier, and Lee Morgan. These artists were the

nucleus of Vee Jay's Jazz Department, and provided many of the earliest jazz albums on the label (see

accompanying discography).

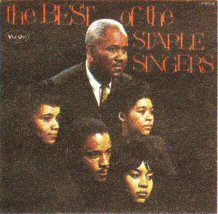

In addition to the Jazz Department, Vee Jay in 1959 began a Gospel series of albums (see discography)

with releases by The Staple Singers, Maceo Woods, The Harmonizing Four, The Swan Silvertones, The

Five Blind Boys, and the Highway QC's. This gospel focus was nothing new, of course, but merely

expanded the considerable efforts Vee Jay had been making in the gospel field since 1953.

In addition to the Jazz Department, Vee Jay in 1959 began a Gospel series of albums (see discography)

with releases by The Staple Singers, Maceo Woods, The Harmonizing Four, The Swan Silvertones, The

Five Blind Boys, and the Highway QC's. This gospel focus was nothing new, of course, but merely

expanded the considerable efforts Vee Jay had been making in the gospel field since 1953.

By 1959, Dee Clark had firmly established himself by regular visits to the R&B top 10 and the pop top

40. But it was a slim year on the charts otherwise. Jimmy Reed was now on the road much of the time

with Al Smith, Red Holloway, and the other band members. This, of course, gave rise to a new round of

Jimmy Reed anecdotes among the Vee Jay staff, the "Jimmy Reed On Tour" stories:

Sid McCoy: "I can remember sitting around on Friday evenings at Vee Jay, after the work day,

sitting around having a taste, and telling stories. More often than not, Jimmy Reed stories would occur.

Al Smith, who was a bass player and producer for Jimmy, went out on the road and kind of looked after

Jimmy Reed. They were someplace playing the ‘chitlin circuit' and Jimmy Reed wanted to drive, and of

course Al was trying to prevent him from doing it. But Jimmy was insistent, and so he gets behind the

wheel anyway...."

Red Holloway: "Well, he ran into a fellow's car. We were in Mississippi, and we were supposed

to play in that town. This fellow jumped out and said, ‘Goddammit, what's the matter with you, fool?

Why in hell don't you watch where you're going?' The guy was really mad. ‘I ain't had this car three

months, and my wife puts one dent in it, and Goddamn, here you put another one on this side!' So

Jimmy got out and said, ‘I's sorry. Look here, I pay for the damage. My name's Jimmy Reed and I....'

‘YOU Jimmy Reed?' ‘Yeah, I'm Jimmy.' ‘Oh, Man! I was just gettin' tickets for your dance tonight!

Man, don't worry 'bout that dent. Hey George! Come look here, this is Jimmy Reed here.' ‘Well, I'll pay

for....' ‘Oh, don't worry 'bout that fender, hell, I'll get it fixed!'

"Another time we were down south, and that's during the time they had a lot of bootleg whiskey and

stuff, and people were dying from this white lightning, because it was homemade and had all kinds of

chemicals in it. Jimmy had bought two gallons of white lightning, and the next day after he bought them

we saw in the paper where about twelve people died, so we showed this to him and told him, ‘You

better pour that stuff out.' This particular state where we were was dry, and we were going to be there for

a week, so that's why Jimmy had bought two gallons. Well, he started crying when he poured it out.

‘This breaks my heart. You don't think just a shot would hurt me?' ‘Well, it might kill you, I don't know.

You can drink it and die....' So he poured it out. Boy, he was a funny cat. There were so many funny

things that happened on the road. He was just a natural country blues singer, and the more he slurred

his words, the better they liked him. But he was one funny cat, believe me. It was quite an experience."

MC: I've heard that Jimmy Reed sometimes went on stage sober, but as the program progressed, he

seemed to become more and more drunk, without any sign that he was drinking anything....

MC: I've heard that Jimmy Reed sometimes went on stage sober, but as the program progressed, he

seemed to become more and more drunk, without any sign that he was drinking anything....

Calvin Carter: "Aw, Jimmy Reed was something else. He had a hose in his harmonica rack,

which led down to his inside coat pocket, where he kept a bottle. He would suck the whiskey up through

that."

Sometimes the stories got pretty far out:

Calvin Carter: "Let me tell you the craziest story ever. We were playing a club in San Francisco,

and Jimmy Reed was getting bald, so he bought a wig. About five minutes before he went on, I told him,

‘Look, Jimmy, you better go in the bathroom, you know, because we don't want to have any problems.'

When Jlmmy had to go, he had to go, know what I mean? So he says, ‘Where is it?' So I pointed and

said, ‘Well, there it is.' Now right next to the bathroom there's a big wall that was mirrored. So after

about four minutes, Jimmy wasn't back, so I started getting nervous, and I went to look for him. So when

I got there, here he was just cussin' and tough, and I said, ‘Hey, Jimmy Reed, you been to the

bathroom yet?' And he says, ‘No." So I said, ‘Well what's the matter man, c'mon!' And he says, ‘I

been asking this cat for the last five minutes where the bathroom is, and he's too ugly to tell me!' And

he'd been looking at himself in the mirror!"

Red Holloway: (Laughs.) "I never heard that one before. I know Jimmy had a wig for awhile, but

that sounds like it's a story."

Sid McCoy: (Laughs.) "The Big Lie."

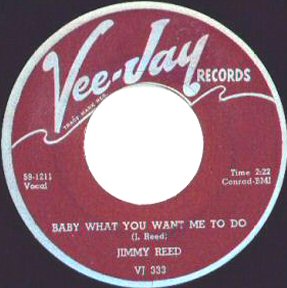

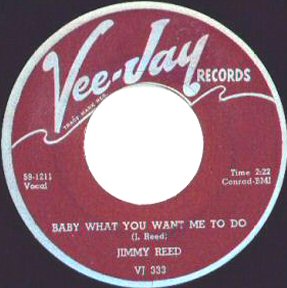

The early years of the 1960s were tremendously successful for Vee Jay. The decade was only a month

old when Jimmy Reed released "Baby What You Want Me To Do," which became a standard for

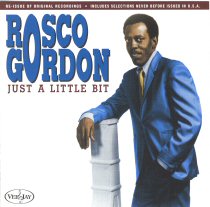

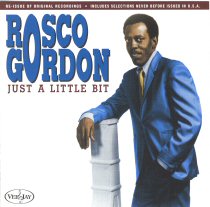

seemingly every rock and roll band in the country during the '60s. Rosco Gordon also made a brief

appearance on the label, but a memorable one:

Calvin Carter: "‘Just A Little Bit' was a really big record. Rosco Gordon was not from

Chicago, he just came through and recorded and I never did get much information on him or get to know

him."

Calvin Carter: "‘Just A Little Bit' was a really big record. Rosco Gordon was not from

Chicago, he just came through and recorded and I never did get much information on him or get to know

him."

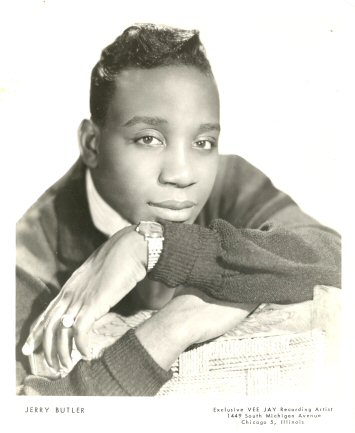

Jerry Butler, who had gone out as a solo act shortly after "For Your Precious Love," had not been able to

come back with a really big hit until he teamed up with Curtis Mayfield and Calvin Carter in 1960 on "He

Will Break Your Heart."

Calvin Carter: "What happened was, I had given the Impressions their release, because I was

never really in love with Curtis Mayfield's voice, I didn't really like that falsetto voice. Well, I gave them a

release because they were bugging me to record without Jerry Butler. I did a couple of things with them,

and Sam (Gooden), who was the bass player, kind of sounded like Jerry Butler, but it was just pseudo.

So I passed on it. Jerry was out on his own, and I told him the best thing he could do was to take Curtis

Mayfield as a guitar player. I never met a guitar player who played the guitar the way Curtis did.

Everything was on open strings, and it sounded very unusual. I don't care where you'd go, you'd always

hear people say, ‘Play me some Curtis Mayfield-type guitar,' and they'd know what you were talking

about. Curtis was also a prolific writer, although he didn't write ‘For Your Precious Love' — that was

Jerry Butler and two guys who were singing with him, the Brooks Brothers. Curtis wrote ‘I'm A-Telling

You,' and he and Jerry and I wrote ‘He Will Break Your Heart.'"

MC: Your name appears on quite a few Vee-Jay records from that period. When you collaborated on

writing these songs, what part did you play in them?

MC: Your name appears on quite a few Vee-Jay records from that period. When you collaborated on

writing these songs, what part did you play in them?

Calvin Carter: "I usually did the lyric. Like on ‘He Will Break Your Heart,' they came in, Jerry

came in, with the hook ‘don't break my heart' or something like that, and I turned it all the way around,

told him, ‘No, put the triangle in there, he will break your heart.' Now we have the hook,

and I'm trying to figure out the first verse, because I basically know we have a song. I would always try to

go back and find a true story in life, and I tried to remember but couldn't come up with anything, so I

started to think about literature. When you think about literature, you got to think about England, and

what's a famous line from literature in England? And it just popped into mind, ‘fare thee well.' The next

line, ‘I know you're leaving for the new love that you've found,' we took because we noticed that on the

road, we would come in and be strangers in town, and we could get all the local chicks. And the guys

they would come with, they would be left outside the dressing room waiting for them to come out from

getting autographs and whatever else they do in dressing rooms. ‘The handsome guy that you've been

dating, I've got a feeling he's gonna put you down, etc.'

"Now Sid McCoy was doing jazz A&R at the time, and he was also doing a syndicated spiritual show. He

was making the tapes for his show in our rehearsal room, in the studios. Sid came back there just as

Jerry and I were there starting on the second verse. Sid was going with a girl that I wanted to go with,

and as we were writing, it popped into my head, ‘He uses all the great quotations. He says all the

things I wish I could say. But he's had so many rehearsals, to him it's just another play.' From there, it

was simple to finish it up, because we were in the theater: ‘When the final act is over, and you're left

standing all alone, when he takes his bow and makes his exit, I'll be there to take you home.' And that

was the song. All of this was done within maybe a twenty minute span."

MC: Great song. It's always been a favorite of mine.

Calvin Carter: "Yes, that song has meant a lot to me. That song has kept me living for the last

five years, because Tony Orlando and Dawn brought it back and it was a huge hit for them, a number

one for maybe three weeks in 1975. Kind of amazed me they got airplay on it."

Things were picking up in general for Vee-Jay: a dozen hits in 1960. In the space of five years, they had

gone from a converted garage on 47th Street to an office building on Michigan Avenue, then to their own

building at 1449 Michigan Avenue. The label itself was looking more prosperous with a rainbow-colored

band around the new black and silver label with a new red and white oval logo.

Things were picking up in general for Vee-Jay: a dozen hits in 1960. In the space of five years, they had

gone from a converted garage on 47th Street to an office building on Michigan Avenue, then to their own

building at 1449 Michigan Avenue. The label itself was looking more prosperous with a rainbow-colored

band around the new black and silver label with a new red and white oval logo.

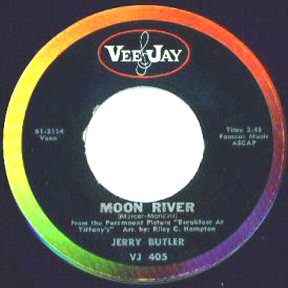

And so it continued in 1961. Jerry Butler and Curtis Mayfield teamed up for two more smashes, "Find

Another Girl" and "I'm A-Telling You." Later in the year, Vee-Jay tried an experiment of sorts with Jerry.

"Moon River," a pop tune taken from the film Breakfast At Tiffany's, had aIreadv been a hit in a

chorale vocaI by Henry Mancini, but Jerry's recording of it was so unique that it scored big with the same

pop audiences that had bought the Mancini version. It soared to #3 on the Easy Listening charts (the first

Vee-Jay record to make those charts), in addition to making the top 15 on both the Hot 100 and R&B

charts, marking the first time Vee Jay had scored in three national charts simultaneously.

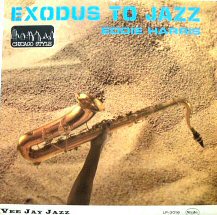

Sid McCoy was responsible for another Vee Jay first during 1961, Eddie Harris' aIbum Exodus to

Jazz stormed up the LP charts to #2. Not only was it the first Vee Jay album to chart nationally, it

was the first time within memory that any jazz album had scored so high.

Sid McCoy was responsible for another Vee Jay first during 1961, Eddie Harris' aIbum Exodus to

Jazz stormed up the LP charts to #2. Not only was it the first Vee Jay album to chart nationally, it

was the first time within memory that any jazz album had scored so high.

Dee Clark started 1961 with "Your Friends," a solid song with a "do-unto-others" moral. Somehow,

"Your Friends" never reached its full sales potential, but in May, Dee came back with his biggest hit ever,

"Raindrops." It was the best selling Vee-Jay single to date, making #2 on the Top 100.

Accompanying "Raindrops" to the top 10 was "Every Beat of My Heart," the debut record by a group

from Georgia called the Pips.

Calvin Carter: "The Pips record was a master acquisition from Atlanta, Georgia. I don't

remember the guy's name, but he sold the record to us, and evidentally the Pips went to New York and

made a deal with Bobby Robinson (Fire/Fury Records). Apparently, the guy's paper wasn't strong

enough to hold them. We didn't want to give Bobby any hassle, so we both had ‘Every Beat of My

Heart' (Vee-Jay's was billed as by the ‘Pips,' while Fury's was by ‘Gladys Knight,' even though both

were really by Gladys Knight and the Pips). Ours went top ten pop, though."

Calvin Carter: "The Pips record was a master acquisition from Atlanta, Georgia. I don't

remember the guy's name, but he sold the record to us, and evidentally the Pips went to New York and

made a deal with Bobby Robinson (Fire/Fury Records). Apparently, the guy's paper wasn't strong

enough to hold them. We didn't want to give Bobby any hassle, so we both had ‘Every Beat of My

Heart' (Vee-Jay's was billed as by the ‘Pips,' while Fury's was by ‘Gladys Knight,' even though both

were really by Gladys Knight and the Pips). Ours went top ten pop, though."

Robinson's record (Fury 1050) topped out at #45, while the Vee Jay version zipped up to #6. Later, of

course, "Gladys Knight and the Pips" became household words.

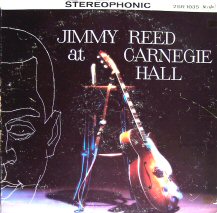

Jimmy Reed put out another classic in 1961, "Big Boss Man," which has been redone by countless

singers and bands, including Elvis Presley. As successful as Jimmy Reed was, there was one place he

just couldn't sell any records: New York City. As Sam Weiss of Old Town Records recalled in an

interview, "Blues records, I mean the authentic, country variety — would not sell in New York. We couldn't

even sell Jimmy Reed in this area, and he's a great blues artist." Thus it was somewhat surprising when

Vee Jay issued Jimmy Reed At Carnegie Hall in mid-1961, a classy double-LP set containing

many of his early hits and a disc of newly-recorded material (Vee Jay 2LP/2SR-1035). Not only was it a

great album, but several of his earlier hits were in true stereo, such as "Big Boss Man" and "Baby What

You Want Me to Do."

MC: As far as I can tell, this record doesn't sound "live" at all.

Calvin Carter: "It wasn't. What happened, we went to New York, I took Jimmy to New York, and

we paid Carnegie Hall for the use of the hall during the day, and we recorded Jimmy there in the hall. It

wasn't live, it was just ‘here's Jimmy Reed in Carnegie Hall.' (Chuckles). We didn't say ‘Jimmy Reed

Live At Carnegie Hall, ‘ we just said ‘Jimmy Reed at Carnegie Hall.' I thought we could get to

use the name, because at that time Carnegie Hall was a very big name in the music business for all your

classical and opera stars and whatever, your big name stars. You know, they'd never have anybody like

Jimmy Reed, who's a country blues singer, in Carnegie Hall, so we just rented the hall for a day and

used it as a studio. I doubt if we could have got ten people in New York to see Jimmy Reed in those

days; we could sell him in Newark and other places, but we could not sell him in New York. We couldn't

get the chance to play him."

Calvin Carter: "It wasn't. What happened, we went to New York, I took Jimmy to New York, and

we paid Carnegie Hall for the use of the hall during the day, and we recorded Jimmy there in the hall. It

wasn't live, it was just ‘here's Jimmy Reed in Carnegie Hall.' (Chuckles). We didn't say ‘Jimmy Reed

Live At Carnegie Hall, ‘ we just said ‘Jimmy Reed at Carnegie Hall.' I thought we could get to

use the name, because at that time Carnegie Hall was a very big name in the music business for all your

classical and opera stars and whatever, your big name stars. You know, they'd never have anybody like

Jimmy Reed, who's a country blues singer, in Carnegie Hall, so we just rented the hall for a day and

used it as a studio. I doubt if we could have got ten people in New York to see Jimmy Reed in those

days; we could sell him in Newark and other places, but we could not sell him in New York. We couldn't

get the chance to play him."

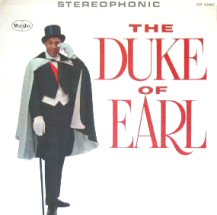

Vee Jay saved its biggest 1961 release for last. Bill "Bunky" Sheppard, an independent producer in

Chicago, was handling both the Sheppards and the Dukays at the time as a production partnership with

Carl Davis in a company called Pam.

Bill Sheppard: "Pam was started a long time ago, back in the '50s, when Carl Davis and I were

partners. We had the group the Sheppards. The group was together before I found them in 1955, and I

don't even recall the name of the group then, but I heard these guys singing on a street corner, and

picked them up that way."

The Sheppards recorded quite a few records, some of which were fairly successful in hometown

Chicago, for a variety of labels.

MC: Did you ever sing with the group? I've read in various places that you did.

Bill Sheppard: "No, no, I didn't sing at all, that's untrue. I think even Time Magazine

made that statement at one time in an article about it, but I know I never did the singing! Carl Davis and I

also had the Dukays at that time. I recorded both ‘Night Owl' and ‘Duke of Earl' for the Nat label, and

they preferred ‘Night Owl,' so I leased the ‘Duke of Earl' master to Vee Jay."

Calvin Carter: "That was a funny story. Gene Chandler was with a group called the Dukays, and

they had a record called ‘Nite Owl' and Bill Sheppard had sent this other tape to the company they

were with, and they passed on it. We recorded in the same studio, and I was in the studio one

day and I heard this song coming out of the mastering room, ‘Duke of Earl.' So I went in there and said,

‘What is that? Who in the hell is that?' He said, ‘That's the Dukays,' and I said, ‘Well, who's

singing?' He told me it was Gene Chandler, and I asked if he was signed with anyone. He said ‘No,'

and I said, ‘Well, let me have the record.' He said, ‘Hey, you got it.' He offered to give me a third of

that record for five hundred dollars, because Carl Davis was his partner at the time. Well, my people

were in Paris, so I called them and told them, ‘Look, I want to pick up this record for Vee Jay.' We

picked up ‘Duke of Earl,' and also the publishing on ‘Nite Owl,' for fifteen hundred dollars. I picked the

record up, but then nothing happened for awhile, because nobody believed in the record but me. I finally

got a release on it at the time of year nobody released records in those days, right before Christmas.

December 11, I think it was. It was really a fast seller. It broke out in Los Angeles at Wallach's Music

City; they had lines around the block and bumper stickers that said ‘Duke of Earl.' Shortly after New

Years (1962), it had sold a million copies. In fact, it was our first million seller."

Calvin Carter: "That was a funny story. Gene Chandler was with a group called the Dukays, and

they had a record called ‘Nite Owl' and Bill Sheppard had sent this other tape to the company they

were with, and they passed on it. We recorded in the same studio, and I was in the studio one

day and I heard this song coming out of the mastering room, ‘Duke of Earl.' So I went in there and said,

‘What is that? Who in the hell is that?' He said, ‘That's the Dukays,' and I said, ‘Well, who's

singing?' He told me it was Gene Chandler, and I asked if he was signed with anyone. He said ‘No,'

and I said, ‘Well, let me have the record.' He said, ‘Hey, you got it.' He offered to give me a third of

that record for five hundred dollars, because Carl Davis was his partner at the time. Well, my people

were in Paris, so I called them and told them, ‘Look, I want to pick up this record for Vee Jay.' We

picked up ‘Duke of Earl,' and also the publishing on ‘Nite Owl,' for fifteen hundred dollars. I picked the

record up, but then nothing happened for awhile, because nobody believed in the record but me. I finally

got a release on it at the time of year nobody released records in those days, right before Christmas.

December 11, I think it was. It was really a fast seller. It broke out in Los Angeles at Wallach's Music

City; they had lines around the block and bumper stickers that said ‘Duke of Earl.' Shortly after New

Years (1962), it had sold a million copies. In fact, it was our first million seller."

With the success of "Duke of Earl," Bill Sheppard joined the Vee Jay staff as a producer, and brought

The Sheppards to the label also. As for the Dukays, some fast shuffling was in order:

Bill Sheppard: "I took Gene Chandler out of the Dukays, and put another person in it and let

Gene go out on his own as The Duke Of Earl."

Vee Jay tried both an answer record ("Duchess of Earl" by The Pearlettes, Vee Jay 435) and a Gene

Chandler followup ("Walk on with the Duke," Vee Jay 440), both of which failed miserably. The Chandler

record, credited to "The Duke Of Earl," was a carbon copy of the hit, and the public wasn't buying.

Calvin Carter: "The Pearlettes were a group I found in Los Angeles. We did one record or so,

but nothing happened. I don't remember too much about them."

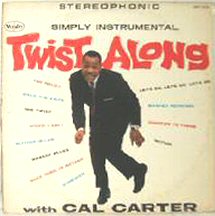

"Duke Of Earl" hit the charts right in the middle of the twist craze. The twist was everywhere, especially

in the music industry. Albums started showing up like Twist With Bobby Darin, Do The Twist With

Ray Charles, Do The Twist With Connie Francis, and . . . well, you get the picture. Vee Jay didn't go

off the deep end with twist records, but there was one particularly interesting item:

MC: I was rummaging through some old WLS top 40 lists from Chicago, and I noticed that in January,

1962, "What'd I Say" by Calvin Carter was on the top 40 there.

MC: I was rummaging through some old WLS top 40 lists from Chicago, and I noticed that in January,

1962, "What'd I Say" by Calvin Carter was on the top 40 there.

Calvin Carter: (Chuckles.) "Oh, yeah. I put a twist album together (Twist Along with Cal

Carter, Vee-Jay LP/SR-1041), I put a band together and did a lot of the current hits instrumentally.

‘What'd I Say' was one of those tunes. Some places the record did all right, and some places It did

nothing; it wasn't a big record."

MC: It seemed to do all right in Chicago.

Calvin Carter: "Well, Chicago was home."

Continued on Page 3...

We would appreciate any additions or corrections to this story. Just send them to us via e-mail. Both Sides Now Publications is an

information web page. We are not a catalog, nor can we provide the records mentioned below. We have

no association with Vee-Jay Records, which is currently inactive. Should you be interested in acquiring

Vee-Jay products (which are all out of print), we suggest you see our Frequently Asked Questions page and Follow the

instructions found there. This story and discography are copyright 1981, 1993, 1997, 1999, 2006 by Mike

Callahan. All rights reserved

Thanks to Robert Pruter and Robert L. Campbell.

Back to the Vee-Jay Main Page

Back to the Vee-Jay Main Page

Back to The Vee-Jay Story, Page 1

Back to The Vee-Jay Story, Page 1

On to The Vee-Jay Story, Page 3

On to The Vee-Jay Story, Page 3

Back to the Discography Listings Page

Back to the Discography Listings Page

Back to the Both Sides Now Home Page

Back to the Both Sides Now Home Page

The Vee-Jay Story, Page 2

The Vee-Jay Story, Page 2

Calvin Carter: "Falcon started roughly in 1957. It started because we were getting more orders,

and for airplay purposes we wanted to get another label, so we used the name Falcon. We later found

out that there was already a label in the south named Falcon, and they brought a suit against us, so we

had to change the name, since they were a union label also. We changed the name of the label to

Abner, although Abner didn't own it, it was owned elusively by Vivian and Jimmy. At that time, we had

the practice of using our name for publishing company names and label names. Of the publishing

companies, Tollie was my middle name, Conrad was Jimmy's middle name, Gladstone was Abner's."

Calvin Carter: "Falcon started roughly in 1957. It started because we were getting more orders,

and for airplay purposes we wanted to get another label, so we used the name Falcon. We later found

out that there was already a label in the south named Falcon, and they brought a suit against us, so we

had to change the name, since they were a union label also. We changed the name of the label to

Abner, although Abner didn't own it, it was owned elusively by Vivian and Jimmy. At that time, we had

the practice of using our name for publishing company names and label names. Of the publishing

companies, Tollie was my middle name, Conrad was Jimmy's middle name, Gladstone was Abner's."

Calvin Carter: "Jerry Butler came in with a group with Curtis Mayfield, called the Impressions.

They came to us on a Saturday. We were distributing our own label in Chicago, so we were open a

half-day on Saturday. Jerry had been all up and down Michigan Boulevard in Chicago trying to record a

record. So they finally came to us, these five guys walked in the door. They sang about five or six

numbers, and sounded pretty good, so I said, ‘Do me a favor. Sing me a song that you wrote, one that

you're almost ashamed to sing in public.' So Jerry says, ‘Hey, let's sing that church type song!' And

Curtis says, ‘No, no, not that one.' I said, ‘Well, let's hear it.' The song was ‘For Your Precious Love.'

I signed them on the spot, and recorded them on the Wednesday after I signed them. Now I took the dub

over to my sister Vivian, and she put it on the air and we got immediate reaction. We also took it over to

the record store and played it over the loudspeakers outside. Now at that time, there was a very big R&B

singer named Roy Hamilton, who had had ‘You'll Never Walk Alone.' Jerry Butler sounded just like him,

and everybody came up and thought it was a new Roy Hamilton record. They asked, ‘Who is it?' and I

said, ‘The Impressions.' But they said, ‘No, who's the singer?' But I didn 't even know their names

then, so I called them into rehearsal and told them to sing the song and got down their names.

Calvin Carter: "Jerry Butler came in with a group with Curtis Mayfield, called the Impressions.

They came to us on a Saturday. We were distributing our own label in Chicago, so we were open a

half-day on Saturday. Jerry had been all up and down Michigan Boulevard in Chicago trying to record a

record. So they finally came to us, these five guys walked in the door. They sang about five or six

numbers, and sounded pretty good, so I said, ‘Do me a favor. Sing me a song that you wrote, one that

you're almost ashamed to sing in public.' So Jerry says, ‘Hey, let's sing that church type song!' And

Curtis says, ‘No, no, not that one.' I said, ‘Well, let's hear it.' The song was ‘For Your Precious Love.'

I signed them on the spot, and recorded them on the Wednesday after I signed them. Now I took the dub

over to my sister Vivian, and she put it on the air and we got immediate reaction. We also took it over to

the record store and played it over the loudspeakers outside. Now at that time, there was a very big R&B

singer named Roy Hamilton, who had had ‘You'll Never Walk Alone.' Jerry Butler sounded just like him,

and everybody came up and thought it was a new Roy Hamilton record. They asked, ‘Who is it?' and I

said, ‘The Impressions.' But they said, ‘No, who's the singer?' But I didn 't even know their names

then, so I called them into rehearsal and told them to sing the song and got down their names.

It was also about that time that Vee Jay welcomed newcomer Wade Flemons, who hit with "Here I

Stand":

It was also about that time that Vee Jay welcomed newcomer Wade Flemons, who hit with "Here I

Stand":

In addition to the Jazz Department, Vee Jay in 1959 began a Gospel series of albums (see discography)

with releases by The Staple Singers, Maceo Woods, The Harmonizing Four, The Swan Silvertones, The

Five Blind Boys, and the Highway QC's. This gospel focus was nothing new, of course, but merely

expanded the considerable efforts Vee Jay had been making in the gospel field since 1953.

In addition to the Jazz Department, Vee Jay in 1959 began a Gospel series of albums (see discography)

with releases by The Staple Singers, Maceo Woods, The Harmonizing Four, The Swan Silvertones, The

Five Blind Boys, and the Highway QC's. This gospel focus was nothing new, of course, but merely

expanded the considerable efforts Vee Jay had been making in the gospel field since 1953.

MC: I've heard that Jimmy Reed sometimes went on stage sober, but as the program progressed, he

seemed to become more and more drunk, without any sign that he was drinking anything....

MC: I've heard that Jimmy Reed sometimes went on stage sober, but as the program progressed, he

seemed to become more and more drunk, without any sign that he was drinking anything....

Calvin Carter: "‘Just A Little Bit' was a really big record. Rosco Gordon was not from

Chicago, he just came through and recorded and I never did get much information on him or get to know

him."

Calvin Carter: "‘Just A Little Bit' was a really big record. Rosco Gordon was not from

Chicago, he just came through and recorded and I never did get much information on him or get to know

him."

MC: Your name appears on quite a few Vee-Jay records from that period. When you collaborated on

writing these songs, what part did you play in them?

MC: Your name appears on quite a few Vee-Jay records from that period. When you collaborated on

writing these songs, what part did you play in them?

Things were picking up in general for Vee-Jay: a dozen hits in 1960. In the space of five years, they had

gone from a converted garage on 47th Street to an office building on Michigan Avenue, then to their own

building at 1449 Michigan Avenue. The label itself was looking more prosperous with a rainbow-colored

band around the new black and silver label with a new red and white oval logo.

Things were picking up in general for Vee-Jay: a dozen hits in 1960. In the space of five years, they had

gone from a converted garage on 47th Street to an office building on Michigan Avenue, then to their own

building at 1449 Michigan Avenue. The label itself was looking more prosperous with a rainbow-colored

band around the new black and silver label with a new red and white oval logo.

Sid McCoy was responsible for another Vee Jay first during 1961, Eddie Harris' aIbum Exodus to

Jazz stormed up the LP charts to #2. Not only was it the first Vee Jay album to chart nationally, it

was the first time within memory that any jazz album had scored so high.

Sid McCoy was responsible for another Vee Jay first during 1961, Eddie Harris' aIbum Exodus to

Jazz stormed up the LP charts to #2. Not only was it the first Vee Jay album to chart nationally, it

was the first time within memory that any jazz album had scored so high.

Calvin Carter: "The Pips record was a master acquisition from Atlanta, Georgia. I don't

remember the guy's name, but he sold the record to us, and evidentally the Pips went to New York and

made a deal with Bobby Robinson (Fire/Fury Records). Apparently, the guy's paper wasn't strong

enough to hold them. We didn't want to give Bobby any hassle, so we both had ‘Every Beat of My

Heart' (Vee-Jay's was billed as by the ‘Pips,' while Fury's was by ‘Gladys Knight,' even though both

were really by Gladys Knight and the Pips). Ours went top ten pop, though."

Calvin Carter: "The Pips record was a master acquisition from Atlanta, Georgia. I don't

remember the guy's name, but he sold the record to us, and evidentally the Pips went to New York and

made a deal with Bobby Robinson (Fire/Fury Records). Apparently, the guy's paper wasn't strong

enough to hold them. We didn't want to give Bobby any hassle, so we both had ‘Every Beat of My

Heart' (Vee-Jay's was billed as by the ‘Pips,' while Fury's was by ‘Gladys Knight,' even though both

were really by Gladys Knight and the Pips). Ours went top ten pop, though."

Calvin Carter: "It wasn't. What happened, we went to New York, I took Jimmy to New York, and

we paid Carnegie Hall for the use of the hall during the day, and we recorded Jimmy there in the hall. It

wasn't live, it was just ‘here's Jimmy Reed in Carnegie Hall.' (Chuckles). We didn't say ‘Jimmy Reed

Live At Carnegie Hall, ‘ we just said ‘Jimmy Reed at Carnegie Hall.' I thought we could get to

use the name, because at that time Carnegie Hall was a very big name in the music business for all your

classical and opera stars and whatever, your big name stars. You know, they'd never have anybody like

Jimmy Reed, who's a country blues singer, in Carnegie Hall, so we just rented the hall for a day and

used it as a studio. I doubt if we could have got ten people in New York to see Jimmy Reed in those

days; we could sell him in Newark and other places, but we could not sell him in New York. We couldn't

get the chance to play him."

Calvin Carter: "It wasn't. What happened, we went to New York, I took Jimmy to New York, and

we paid Carnegie Hall for the use of the hall during the day, and we recorded Jimmy there in the hall. It

wasn't live, it was just ‘here's Jimmy Reed in Carnegie Hall.' (Chuckles). We didn't say ‘Jimmy Reed

Live At Carnegie Hall, ‘ we just said ‘Jimmy Reed at Carnegie Hall.' I thought we could get to

use the name, because at that time Carnegie Hall was a very big name in the music business for all your

classical and opera stars and whatever, your big name stars. You know, they'd never have anybody like

Jimmy Reed, who's a country blues singer, in Carnegie Hall, so we just rented the hall for a day and

used it as a studio. I doubt if we could have got ten people in New York to see Jimmy Reed in those

days; we could sell him in Newark and other places, but we could not sell him in New York. We couldn't

get the chance to play him."

Calvin Carter: "That was a funny story. Gene Chandler was with a group called the Dukays, and

they had a record called ‘Nite Owl' and Bill Sheppard had sent this other tape to the company they

were with, and they passed on it. We recorded in the same studio, and I was in the studio one

day and I heard this song coming out of the mastering room, ‘Duke of Earl.' So I went in there and said,

‘What is that? Who in the hell is that?' He said, ‘That's the Dukays,' and I said, ‘Well, who's

singing?' He told me it was Gene Chandler, and I asked if he was signed with anyone. He said ‘No,'

and I said, ‘Well, let me have the record.' He said, ‘Hey, you got it.' He offered to give me a third of

that record for five hundred dollars, because Carl Davis was his partner at the time. Well, my people

were in Paris, so I called them and told them, ‘Look, I want to pick up this record for Vee Jay.' We

picked up ‘Duke of Earl,' and also the publishing on ‘Nite Owl,' for fifteen hundred dollars. I picked the

record up, but then nothing happened for awhile, because nobody believed in the record but me. I finally

got a release on it at the time of year nobody released records in those days, right before Christmas.

December 11, I think it was. It was really a fast seller. It broke out in Los Angeles at Wallach's Music

City; they had lines around the block and bumper stickers that said ‘Duke of Earl.' Shortly after New

Years (1962), it had sold a million copies. In fact, it was our first million seller."

Calvin Carter: "That was a funny story. Gene Chandler was with a group called the Dukays, and

they had a record called ‘Nite Owl' and Bill Sheppard had sent this other tape to the company they

were with, and they passed on it. We recorded in the same studio, and I was in the studio one

day and I heard this song coming out of the mastering room, ‘Duke of Earl.' So I went in there and said,

‘What is that? Who in the hell is that?' He said, ‘That's the Dukays,' and I said, ‘Well, who's

singing?' He told me it was Gene Chandler, and I asked if he was signed with anyone. He said ‘No,'

and I said, ‘Well, let me have the record.' He said, ‘Hey, you got it.' He offered to give me a third of

that record for five hundred dollars, because Carl Davis was his partner at the time. Well, my people

were in Paris, so I called them and told them, ‘Look, I want to pick up this record for Vee Jay.' We

picked up ‘Duke of Earl,' and also the publishing on ‘Nite Owl,' for fifteen hundred dollars. I picked the

record up, but then nothing happened for awhile, because nobody believed in the record but me. I finally

got a release on it at the time of year nobody released records in those days, right before Christmas.

December 11, I think it was. It was really a fast seller. It broke out in Los Angeles at Wallach's Music

City; they had lines around the block and bumper stickers that said ‘Duke of Earl.' Shortly after New

Years (1962), it had sold a million copies. In fact, it was our first million seller."

MC: I was rummaging through some old WLS top 40 lists from Chicago, and I noticed that in January,

1962, "What'd I Say" by Calvin Carter was on the top 40 there.

MC: I was rummaging through some old WLS top 40 lists from Chicago, and I noticed that in January,

1962, "What'd I Say" by Calvin Carter was on the top 40 there.

Back to the Vee-Jay Main Page

Back to the Vee-Jay Main Page  Back to The Vee-Jay Story, Page 1

Back to The Vee-Jay Story, Page 1  On to The Vee-Jay Story, Page 3

On to The Vee-Jay Story, Page 3  Back to the Discography Listings Page

Back to the Discography Listings Page  Back to the Both Sides Now Home Page

Back to the Both Sides Now Home Page