By 1975, when I first happened upon the store, it was already a "happening" place. I was taking some short courses at UCLA when I spied the store from a bus on my way back to the hotel. There seemed to be a brisk business, so the next day, I got off at that stop and wandered in along with the rest of the collectors and music fans. It was a surprising store from a number of aspects, most of which were unknown at the time but widely imitated later. First, there was a selection of used records at reasonable prices. Then there was the large number of import albums, and even sections for obscure (to me, at least) local music. And to top it off, there were little knots of knowledgeable conversation going on between customers and the store employees. And unlike the Greenwich Village shops in Manhattan, they were talking about a lot wider variety of music than just doo-wops (this was 1975, the days of Bim Bam Boom and other fledgling collectors mags, usually devoted to r&b and doo-wop).

There was no doubt that the store employees kept an ear on what was going on in the music business,

but that also applied to what was going on in clubs, universities, and even street musicians in the greater

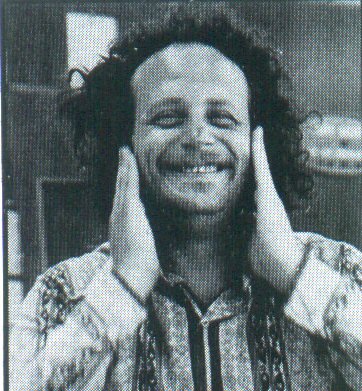

L.A. area. The employees became fans of a street musician named Larry "Wild Man" Fischer, a

songwriter who could churn out songs about any subject on demand. They were not necessarily great

songs, but they were almost always entertaining. Fischer was also a store customer, and store manager

Harold Bronson recorded him in the back room of the store in 1975 on a cassette recorder singing a self-

penned off-key ditty called "Go to Rhino Records." Although Bronson and Foos saw little more than a

funny promotion in this, the song got around, and before long, they got an order for 500 copies from

England, where it was being played on the radio!

There was no doubt that the store employees kept an ear on what was going on in the music business,

but that also applied to what was going on in clubs, universities, and even street musicians in the greater

L.A. area. The employees became fans of a street musician named Larry "Wild Man" Fischer, a

songwriter who could churn out songs about any subject on demand. They were not necessarily great

songs, but they were almost always entertaining. Fischer was also a store customer, and store manager

Harold Bronson recorded him in the back room of the store in 1975 on a cassette recorder singing a self-

penned off-key ditty called "Go to Rhino Records." Although Bronson and Foos saw little more than a

funny promotion in this, the song got around, and before long, they got an order for 500 copies from

England, where it was being played on the radio!

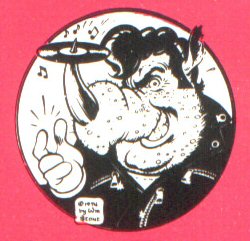

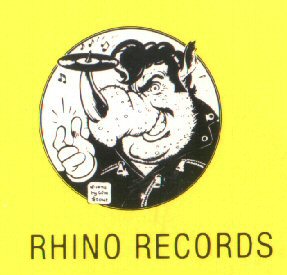

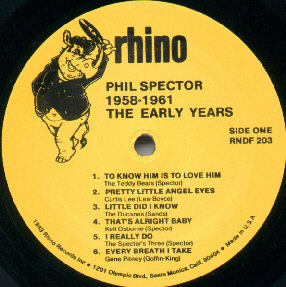

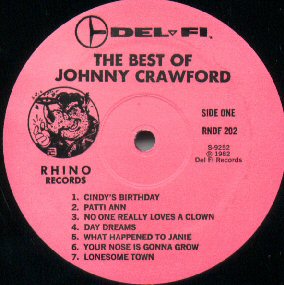

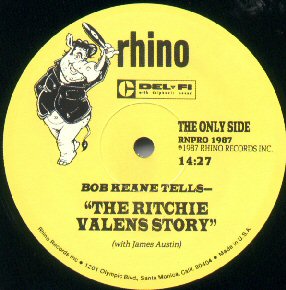

In 1974, Foos and Bronson had had cartoonist William Stout (very well known for work with the Firesign

Theatre and for drawing covers of -ahem - independently pressed albums) draw "Rocky the Rhino" as

their logo, and so in 1977, with the Fischer tune and a logo, they were off and running as a record label.

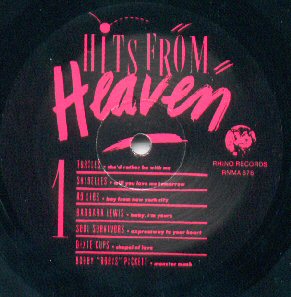

The first years of Rhino Records' output (1977-1985) were a perfect reflection of the store: eclectic,

eccentric, and fun. There were lots of novelties (and nearby radio personality Barry Hansen, aka Dr.

Demento, noticed these right away and visited for the latest material), surf records, local new wave

groups, and eventually a slew of colored vinyl, oddly-shaped records, and picture discs, and a

few reissues of albums previously released on other labels but at the time long out of print.

In 1974, Foos and Bronson had had cartoonist William Stout (very well known for work with the Firesign

Theatre and for drawing covers of -ahem - independently pressed albums) draw "Rocky the Rhino" as

their logo, and so in 1977, with the Fischer tune and a logo, they were off and running as a record label.

The first years of Rhino Records' output (1977-1985) were a perfect reflection of the store: eclectic,

eccentric, and fun. There were lots of novelties (and nearby radio personality Barry Hansen, aka Dr.

Demento, noticed these right away and visited for the latest material), surf records, local new wave

groups, and eventually a slew of colored vinyl, oddly-shaped records, and picture discs, and a

few reissues of albums previously released on other labels but at the time long out of print.

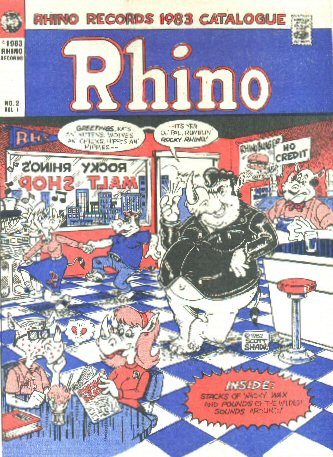

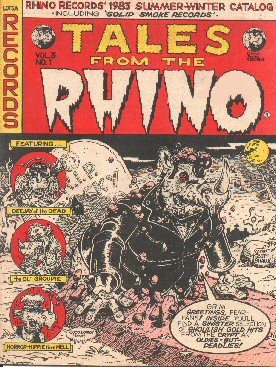

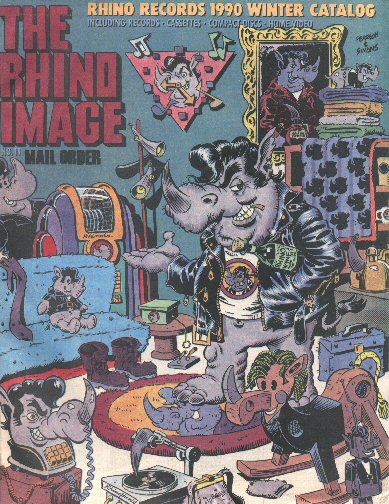

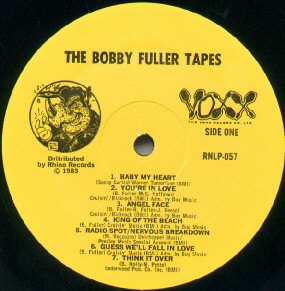

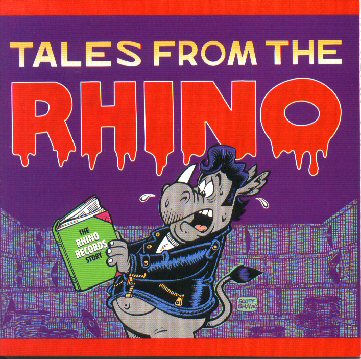

Early 1980s catalogues, with full color covers by Scott Shaw (today a very well known cartoonist), looked

in every way like comic books, from the "Comics Code Authority" knockoff in the upper right corner to

the cheap pulp paper inside. One expected to see someone kicking sand in the face of a Charles Atlas

protegee on the inside back cover, but instead there was a baseball-card-like check list of Rhino's

releases (collect them all!). From a record collector's/discographer's viewpoint, Rhino Records gave

every indication of being a prototype for a label that was not going to be around very long. Even their

record numbering sequences reflected the store's less-than-serious nature. Series started at RNLP-001,

050, 100, 150, 200, 250, 280, 300, 400, 500 ... well, you get the picture. And not only did they seemingly

start a new series for every whim, some of the numbering sequences went backwards or even

backwards and forwards interchangeably! I suppose that if they had known they would eventually issue

thousands of albums, the initial planning may have been more structured (Right. Like 001, 500, 1000,

1500, etc.). Some multi-disc sets were numbered for their retail price, then others like them were

numbered up and down from there!

Early 1980s catalogues, with full color covers by Scott Shaw (today a very well known cartoonist), looked

in every way like comic books, from the "Comics Code Authority" knockoff in the upper right corner to

the cheap pulp paper inside. One expected to see someone kicking sand in the face of a Charles Atlas

protegee on the inside back cover, but instead there was a baseball-card-like check list of Rhino's

releases (collect them all!). From a record collector's/discographer's viewpoint, Rhino Records gave

every indication of being a prototype for a label that was not going to be around very long. Even their

record numbering sequences reflected the store's less-than-serious nature. Series started at RNLP-001,

050, 100, 150, 200, 250, 280, 300, 400, 500 ... well, you get the picture. And not only did they seemingly

start a new series for every whim, some of the numbering sequences went backwards or even

backwards and forwards interchangeably! I suppose that if they had known they would eventually issue

thousands of albums, the initial planning may have been more structured (Right. Like 001, 500, 1000,

1500, etc.). Some multi-disc sets were numbered for their retail price, then others like them were

numbered up and down from there!

By the mid-1980s, Bill Inglot was doing the production on many of the Rhino reissues, Ken Perry was mastering, and Gary Stewart and James Austin were doing A&R. Despite the fun-loving approach, the product was being taken seriously, and Rhino's vinyl issues were generally excellent quality. The label was financially stable, although as the principals noted, no one was getting rich. Then, near the end of 1985, Rhino reached a turning point.

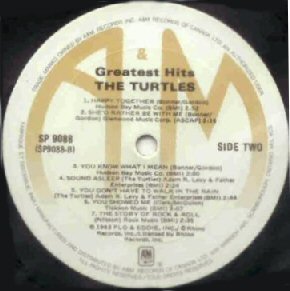

In the early days, Rhino basically arranged their own distribution, both in the U.S. and outside this

country. Some of Rhino's albums were issued in Canada on the A&M label (see 1983 example at left),

but with the regular Rhino cover. Rhino Records may have eventually become merely a novelty footnote

in the history of music were it not for a deal struck with Capitol Records, a major label based in

neighboring Hollywood. Capitol agreed to distribute Rhino starting in 1986, a deal which lasted six years

to 1992. As part of the deal, Rhino has easy access to most of the Capitol back catalog, and began

offering many reissues of albums from that catalog. Along with the change in distribution, the Rhino

catalog numbers for new product changed, adding "70" in front of the three-digit numbers Rhino had

been using. This was in keeping with Capitol's numbering system which used a 5-digit number (usually

starting with "7") for record releases. They eventually dropped the RNLP-/RNC-/RNCD- prefixs for LPs,

cassettes, and CDs, also, in favor of Capitol's R1/R2/R4 prefixes for LPs, CDs, and cassettes.

In the early days, Rhino basically arranged their own distribution, both in the U.S. and outside this

country. Some of Rhino's albums were issued in Canada on the A&M label (see 1983 example at left),

but with the regular Rhino cover. Rhino Records may have eventually become merely a novelty footnote

in the history of music were it not for a deal struck with Capitol Records, a major label based in

neighboring Hollywood. Capitol agreed to distribute Rhino starting in 1986, a deal which lasted six years

to 1992. As part of the deal, Rhino has easy access to most of the Capitol back catalog, and began

offering many reissues of albums from that catalog. Along with the change in distribution, the Rhino

catalog numbers for new product changed, adding "70" in front of the three-digit numbers Rhino had

been using. This was in keeping with Capitol's numbering system which used a 5-digit number (usually

starting with "7") for record releases. They eventually dropped the RNLP-/RNC-/RNCD- prefixs for LPs,

cassettes, and CDs, also, in favor of Capitol's R1/R2/R4 prefixes for LPs, CDs, and cassettes.

The distribution deal with Capitol had an even greater impact on Rhino's future in 1989. When Roulette Records owner Morris Levy ran into financial difficulties and needed to sell off the label he had owned since its inception in 1957, Rhino was interested. But the price was high. Rhino and EMI (Capitol's parent company in England) agreed to jointly buy the Roulette label, with Rhino owning US rights and EMI having the rights overseas, allowing Rhino to acquire a vast catalog for reissues that it owned outright. The late Bob Hyde, who had run Murray Hill Records as a division of Random House Books in the late 1970s and 1980s, became a valuable consultant to Rhino about what they had bought. Hyde and Boston-based deejay "Little" Walter DeVenne had been all through the Roulette vaults during the days Murray Hill was leasing from Roulette, and helped design a series of reissues of Roulette/End/Gone/Gee/Colpix/Dimension material for Rhino's Bill Inglot to remaster. By 1990, Rhino hired Hyde to oversee the Rhino mail order catalog, which had become a substantial part of their business. (Hyde later left Rhino and became head of Capitol's reissue division).

With access to the Roulette family of labels, and the Capitol family of labels, and Bill Inglot scouring the country for independent label tapes to reissue, and the general high quality of the product, Rhino quickly became the best-known reissue label in the business, especially for CDs. By 1989, it was obvious to folks at Rhino that vinyl was on the way out and CDs were the future of reissues in the 1990s. They drastically cut back on the number of vinyl albums pressed for new offerings, and made some of the issues cassette-and-CD only. By 1990, there were few new vinyl issues offered, and by early 1991, they were advertising their "Final Vinyl Sale" of remaining stock at closeout prices. It was interesting that almost none of the closeout albums were the recent vinyl issues, meaning they had pressed few enough that there was little if any costly overstock.

By 1990, Rhino was issuing CD product at a furious rate, and the vast majority of this product was

reissues of "oldies," often with CD bonus tracks, newly remastered stereo versions of songs, and

previously unissued goodies. By 1992, the Capitol distribution contract was ending, and Rhino got an

offer from Time-Warner, Inc. that they couldn't refuse. Warner-Elektra-Atlantic (WEA) would distribute

Rhino product, and Time-Warner would purchase of half the Rhino label. They would leave the Rhino

management intact (at least, sign them to standard 5 year management contracts), and put Rhino in

charge of reissuing the extensive Atlantic Records catalog. To the Rhino execs, who had grown up

hearing Atlantic Records on the radio, it was the opportunity of a lifetime. As it turned out, this deal was

both a blessing and a headache for Rhino.

By 1990, Rhino was issuing CD product at a furious rate, and the vast majority of this product was

reissues of "oldies," often with CD bonus tracks, newly remastered stereo versions of songs, and

previously unissued goodies. By 1992, the Capitol distribution contract was ending, and Rhino got an

offer from Time-Warner, Inc. that they couldn't refuse. Warner-Elektra-Atlantic (WEA) would distribute

Rhino product, and Time-Warner would purchase of half the Rhino label. They would leave the Rhino

management intact (at least, sign them to standard 5 year management contracts), and put Rhino in

charge of reissuing the extensive Atlantic Records catalog. To the Rhino execs, who had grown up

hearing Atlantic Records on the radio, it was the opportunity of a lifetime. As it turned out, this deal was

both a blessing and a headache for Rhino.

On the good side, with yet another major catalog (Atlantic) to choose from, Rhino product issues and sales again surged, as Rhino became the reissue arm for a huge conglomerate. And Time-Warner left Rhino alone to do its thing the way it knew best, without interfering with the content or quality of the Rhino product. But the corporate atmosphere of the music business was a far cry from the informal atmosphere of the Rhino Records store of 10-15 years earlier, and tiring of the bureaucracy, some of the Rhino executives left when their contracts expired. And in 1998, Time-Warner exercised a clause in the 1992 agreement that allowed them to purchase the remaining 50% of Rhino. Ironically, in 1992 even the store was part of the deal, as Time-Warner took over ownership of the Rhino Records store! But through the mystery of legal fine print, after the 1998 buyout, the store reverted to Richard Foos!

Today, although Foos and Bronson have moved on to other things, many of the Rhino staff is still at the

label. Rhino Records is part of the gigantic WEA conglomerate, and is putting out product as always. But

as a corporate giant, some of the things the early Rhino was known for are gone. The logo has changed

from the Rocky Rhino cartoon to a more sedate oval. The early Rhino management was known to

support environmental and humanitarian causes, and put little blurbs into LPs and CDs inviting

customers to join them in donating to these. And whereas the Rhino Records of the late 1970s and

early 1980s was primarily an outlet for new music and truly off-the-wall things like kazoo bands, today's

Rhino Records has found the niche of a reissue label. That said, I think we will all agree that if Rhino

Records had never existed, we would all have been the poorer for it.

Today, although Foos and Bronson have moved on to other things, many of the Rhino staff is still at the

label. Rhino Records is part of the gigantic WEA conglomerate, and is putting out product as always. But

as a corporate giant, some of the things the early Rhino was known for are gone. The logo has changed

from the Rocky Rhino cartoon to a more sedate oval. The early Rhino management was known to

support environmental and humanitarian causes, and put little blurbs into LPs and CDs inviting

customers to join them in donating to these. And whereas the Rhino Records of the late 1970s and

early 1980s was primarily an outlet for new music and truly off-the-wall things like kazoo bands, today's

Rhino Records has found the niche of a reissue label. That said, I think we will all agree that if Rhino

Records had never existed, we would all have been the poorer for it.

This discography was constructed from our record collections, a series of Rhino catalogs, and other primary research done by the authors. Although we have no association with Rhino Records, Both Sides Now is grateful to Bob Hyde and Rhino Records for listing the first edition of "Oldies on CD" in their early 1990s catalogs, which greatly publicized BSN when we were struggling to "make it." I think they understood what starting out in a big industry is all about.

The Rhino Records Story

The Rhino Records Story

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 1 001 & 70000 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 1 001 & 70000 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 2 100 & 70100 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 2 100 & 70100 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 3 200 & 70200 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 3 200 & 70200 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 4 300 & 70300 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 4 300 & 70300 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 5 400 & 70400 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 5 400 & 70400 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 6 500 & 70500 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 6 500 & 70500 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 7 600 & 70600 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 7 600 & 70600 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 8 700 & 70700 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 8 700 & 70700 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 9 800 & 70800 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 9 800 & 70800 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 10 900 & 70900 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 10 900 & 70900 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 11 71000 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 11 71000 Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 12 Miscellaneous Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 12 Miscellaneous Series

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 13 Early Compact Discs

On to the Rhino Discography, Part 13 Early Compact Discs

Back to the Warner Brothers Records Story

Back to the Warner Brothers Records Story

Back to the Discography Listings Page

Back to the Discography Listings Page