Bogart initially financed the label partly through borrowing some cash from Warner Brothers Records, who in return set up a deal to distribute the new label's product. Bogart had been successful, first at Cameo-Parkway and then at Buddah, so it looked like a good investment for Warners. The Casablanca offices were originally at 1112 N. Sherbourne Drive in Los Angeles. The first eight LPs were all issued between February and August, 1974, under the NB-9000 series (with the "NB" prefix, of course, standing for the all-too-modest Neil Bogart. The single prefix was "NEB-").

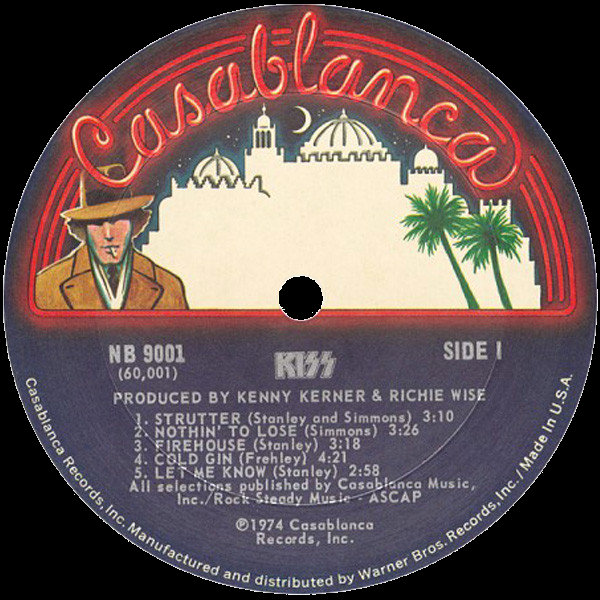

The first signing on the label was the then-unknown rock group Kiss in November, 1973. The group's act included facial makeup and some musically basic but well-crafted proto-heavy metal music. They had spent their time before getting a contract playing in bars in Queens. Bogart brought them to California and added some effects from the local magic store to their stage act. Their first LP was recorded and set for release in February, 1974.

Meanwhile, Casablanca signed a few other acts, and put out their first single around the first of the year,

1974. The debut single for the label was "Virginia (Touch Me Like You Do)" [Casablanca 0001, a lease

of Canadian single Yorkville 100] by Bill Amesbury, a 25-year-old Canadian singer who was a veteran of

the Toronto music scene. The single slowly inched up the charts, finally reaching #59 in March.

Amesbury proved to be a one-hit wonder here in the US, although "Virginia" went top-10 in Canada and

he had other hits in Canada and Europe.

Meanwhile, Casablanca signed a few other acts, and put out their first single around the first of the year,

1974. The debut single for the label was "Virginia (Touch Me Like You Do)" [Casablanca 0001, a lease

of Canadian single Yorkville 100] by Bill Amesbury, a 25-year-old Canadian singer who was a veteran of

the Toronto music scene. The single slowly inched up the charts, finally reaching #59 in March.

Amesbury proved to be a one-hit wonder here in the US, although "Virginia" went top-10 in Canada and

he had other hits in Canada and Europe.

Bogart followed up Amesbury's single with non-chart offerings by the Bob Crewe Generation,

Parliament, and Kiss, and several others. Gloria Scott's "What Am I Gonna Do" [Casablanca 0005]

managed to reach #74 on the R&B charts starting in April, but that, too, was short lived. By May,

Casablanca finally managed to get a Kiss single on the charts - mainly due to album sales from FM

airplay - but "Kissin' Time" [Casablanca 0011] only reached #83. The all-girl rock group Fanny likewise

hit the bottom reaches of the charts with "I've Had It" [Casablanca 0009], which reached #74 in June,

and Greg Perry managed #81 on the R&B charts in August with "Boogie Man" [Casablanca 0019].

Parliament's "Up for the Down Stroke" [Casablanca 0013], had been released in May, but was doing

nothing at all.

Bogart followed up Amesbury's single with non-chart offerings by the Bob Crewe Generation,

Parliament, and Kiss, and several others. Gloria Scott's "What Am I Gonna Do" [Casablanca 0005]

managed to reach #74 on the R&B charts starting in April, but that, too, was short lived. By May,

Casablanca finally managed to get a Kiss single on the charts - mainly due to album sales from FM

airplay - but "Kissin' Time" [Casablanca 0011] only reached #83. The all-girl rock group Fanny likewise

hit the bottom reaches of the charts with "I've Had It" [Casablanca 0009], which reached #74 in June,

and Greg Perry managed #81 on the R&B charts in August with "Boogie Man" [Casablanca 0019].

Parliament's "Up for the Down Stroke" [Casablanca 0013], had been released in May, but was doing

nothing at all.

Things on the album side weren't much better. Kiss [Casablanca NB 9001] hopped on the charts

in April, and made it to #87, a decent if not spectacular showing. Parliament's first album, Up for the

Down Stroke [Casablanca NB 9003] initially didn't chart at all. A T.Rex album, Light of Love

[Casablanca NB 9006] reached #205 and died. Nothing seemed to be really working.

Things on the album side weren't much better. Kiss [Casablanca NB 9001] hopped on the charts

in April, and made it to #87, a decent if not spectacular showing. Parliament's first album, Up for the

Down Stroke [Casablanca NB 9003] initially didn't chart at all. A T.Rex album, Light of Love

[Casablanca NB 9006] reached #205 and died. Nothing seemed to be really working.

Bogart was disillusioned with Warner Brothers' promotion efforts on his behalf, and since the management of Casablanca was all recruited from the promotion side of the business, Bogart was sure he and his crew could do better on their own. He approached Warner Brothers in the summer of 1974 and requested that he be released from the promotion deal, and agreed to pay back the financial loan as quickly as feasible. At this point, Casablanca had been in business the better part of a year and hadn't had anything even resembling a real hit. Warner's management knew a dud when they saw one, and agreed to let Bogart and his label go, provided they paid back the loan promptly.

Bogart switched the singles series from the 0001 series to the 0100 series and the albums to the 7000

series, and went to work pushing product. The previously issued albums were reissued on the 7000

series, and the singles that were still selling were reissued on the 0100 series. Simon Stokes' "Captain

Howdy," erstwhile Casablanca 0007 but now Casablanca 0102, reached #90 in July, and Herman's

Hermits' lead singer Peter Noone's try for a comeback with "Meet Me on the Corner Down at Joe's

Café" [Casablanca 0016/0106] stalled at #101 in September. More importantly, Parliament's "Up

for the Down Stroke," now renumbered Casablanca 0104, hopped on the R&B charts and eventually

reached #10, making it to #63 on the pop charts and pulling up sales for the renumbered album

[Casablanca NBLP-7002], which reached #19 on the R&B charts and #201 on the pop side. An eerie

John-Lennon-soundalike single called "So You Are A Star" by the Hudson Brothers was issued as

Casablanca 0108, and looked like it would be the biggest Casablanca hit to date.

Bogart switched the singles series from the 0001 series to the 0100 series and the albums to the 7000

series, and went to work pushing product. The previously issued albums were reissued on the 7000

series, and the singles that were still selling were reissued on the 0100 series. Simon Stokes' "Captain

Howdy," erstwhile Casablanca 0007 but now Casablanca 0102, reached #90 in July, and Herman's

Hermits' lead singer Peter Noone's try for a comeback with "Meet Me on the Corner Down at Joe's

Café" [Casablanca 0016/0106] stalled at #101 in September. More importantly, Parliament's "Up

for the Down Stroke," now renumbered Casablanca 0104, hopped on the R&B charts and eventually

reached #10, making it to #63 on the pop charts and pulling up sales for the renumbered album

[Casablanca NBLP-7002], which reached #19 on the R&B charts and #201 on the pop side. An eerie

John-Lennon-soundalike single called "So You Are A Star" by the Hudson Brothers was issued as

Casablanca 0108, and looked like it would be the biggest Casablanca hit to date.

For the second time in a few months, Bogart renumbered the singles series, now to the 800 series, and reissued the Hudson Brothers, Peter Noone, and Parliament 45s to 801, 802, and 803 respectively. As Casablanca 801, the Hudson Brothers single cracked the top-30, finally reaching #21 in the fall.

Bogart paid Warner Brothers back, but by November, 1974, the label was so strapped for cash that they

almost went under. To bring in some revenue, Bogart turned to the industry tried-and-true cash cow: the

"special products album." These usually make good money because the record company has virtually

no studio cost. Manheim Fox and Jeff Franklin arranged with NBC to access their back catalog of

Tonight Show programs, and Casablanca employees Joyce Biawitz (soon to be Mrs. Neil Bogart)

and Bernard Fox produced a "special products" album called Here's Johnny: Magic Moments from

the Tonight Show [SPNB 1296]. Casablanca advertised this album heavily, and the promoters

promoted their socks off - this was going to be one of the biggest selling albums ever!

Bogart paid Warner Brothers back, but by November, 1974, the label was so strapped for cash that they

almost went under. To bring in some revenue, Bogart turned to the industry tried-and-true cash cow: the

"special products album." These usually make good money because the record company has virtually

no studio cost. Manheim Fox and Jeff Franklin arranged with NBC to access their back catalog of

Tonight Show programs, and Casablanca employees Joyce Biawitz (soon to be Mrs. Neil Bogart)

and Bernard Fox produced a "special products" album called Here's Johnny: Magic Moments from

the Tonight Show [SPNB 1296]. Casablanca advertised this album heavily, and the promoters

promoted their socks off - this was going to be one of the biggest selling albums ever!

The hype worked. There were so many pre-release orders for it that it "shipped gold," that is, the orders would account for gold record status for sales right out of the gate. Well, they would have qualified for gold status, that is, if the albums had actually sold, but as it turned out, they didn't. At that time, distributors could return albums for full refund if they didn't sell. Unsold albums came back in such quantity that comedian Robert Klein wryly observed that the record "shipped gold, and came back platinum."

No matter. The orders had provided a huge cash flow boost for Casablanca, and they were back running at full speed. They owed money, but that was the future. Bogart moved the corporate offices to 8255 Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, where he built new buildings and styled the offices after the movie set of the Humphrey Bogart film Casablanca. Everybody got a leased Mercedes.

The records still weren't big hits, though, and though 1975 looked a bit better than 1974, it was no barn

burner. Parliament remade their #3 hit from eight years earlier ["(I Wanna) Testify," Revilot 207] as

"Testify" [Casablanca 811], but it received a tepid response even on the R&B charts, where it only

managed #77. James and Bobby Purify came through with a #30 R&B hit with "Do Your Thing"

[Casablanca 812], but it proved to be a hit without a successful followup. Gloria Scott reached #14 on

the R&B charts with "Just as Long as We're Together" [Casablanca 815], but like the Purifys, it was her

last chart record.

The records still weren't big hits, though, and though 1975 looked a bit better than 1974, it was no barn

burner. Parliament remade their #3 hit from eight years earlier ["(I Wanna) Testify," Revilot 207] as

"Testify" [Casablanca 811], but it received a tepid response even on the R&B charts, where it only

managed #77. James and Bobby Purify came through with a #30 R&B hit with "Do Your Thing"

[Casablanca 812], but it proved to be a hit without a successful followup. Gloria Scott reached #14 on

the R&B charts with "Just as Long as We're Together" [Casablanca 815], but like the Purifys, it was her

last chart record.

By spring of 1975, Casablanca's main rock group, Kiss, and main funk group, Parliament, were almost

unknown to the record-buying public at large. Kiss was getting FM airplay and Parliament was known to

the listeners of soul stations, but neither had really broken out yet to the superstardom that awaited. Kiss'

second album, Hotter than Hell [Casablanca NBLP-7006] had managed to reach #100 early in

1975, but it was not all the Casablanca promotional department had hoped. A live version of Kiss' "Rock

and Roll All Nite" [Casablanca 829] was issued in the spring, but it only reached #68. Likewise,

Parliament's "Chocolate City" [Casablanca 831] scored moderately well on the R&B charts at #24, but

only reached #94 on the pop charts. Their followup, "Ride On" [Casablanca 843], only made #64 on the

R&B charts and missed the pop stations completely.

By spring of 1975, Casablanca's main rock group, Kiss, and main funk group, Parliament, were almost

unknown to the record-buying public at large. Kiss was getting FM airplay and Parliament was known to

the listeners of soul stations, but neither had really broken out yet to the superstardom that awaited. Kiss'

second album, Hotter than Hell [Casablanca NBLP-7006] had managed to reach #100 early in

1975, but it was not all the Casablanca promotional department had hoped. A live version of Kiss' "Rock

and Roll All Nite" [Casablanca 829] was issued in the spring, but it only reached #68. Likewise,

Parliament's "Chocolate City" [Casablanca 831] scored moderately well on the R&B charts at #24, but

only reached #94 on the pop charts. Their followup, "Ride On" [Casablanca 843], only made #64 on the

R&B charts and missed the pop stations completely.

It was in the early summer of 1975 that I first heard a Kiss record. I was working at a top-40 station and the promo man had brought in "C'Mon and Love Me" [Casablanca 841]. Although our Program Director thought it a bit too risqué for our audience, I told him that there was something about this group that was unusual and catchy, and that they would probably be heard from in the future. It was simplistic rock, almost teenybopperish in lyric, but they did it really well. And this was without seeing their theatrical appearance! Sure enough, it was Kiss who finally broke through with the first legitimate Casablanca hit near the end of 1975, with a studio recording of "Rock and Roll All Nite" [Casablanca 850], which reached #12 on the pop charts.

It was about this time, the last few months of 1975, that some critical decisions were made at

Casablanca that would affect the future of Casablanca and even pop music in general. Neil Bogart had

met Italian-born artist/producer Giorgio Moroder, who with his partner Pete Bellotte, had set up shop in

Munich, Germany, running their label called Oasis. Moroder and Bellotte were mixing dance music for

European audiences, music that was played in dance halls (discotheques) across the continent. The

music - tagged "Euro-Disco" eventually - caught Bogart's attention. Bogart agreed to distribute the Oasis

label here in the US. The first single Moroder offered was a disco record by Boston-born singer Donna

Summer called "Love to Love You" [Oasis 401], a suggestive if not downright erotic dance groove. When

first released, it didn't sell quickly. Bogart played the new record for the dance crowd at one of

Casablanca's never-ending parties, and they demanded that it be played over and over so they could

keep in that groove. Bogart called Moroder in Germany and asked if he could come up with a much

longer version, and Moroder responded with a version that ran almost 17 minutes! He also requested

the title be changed slightly to, "Love to Love You, Baby." Bogart put the 17-minute disco blockbuster on

one side of the first Donna Summer album, and shipped promo copies to disc jockeys at clubs, making it

arguably the first 12-inch disco single. Sales from the clubs drove the single up the charts, where it

eventually made #2 (#3 R&B) in early 1976. This led to special long disco versions of singles, given to

deejays on 12-inch records, becoming standard fare in the music promotion world. Although they had

dabbled in several musical genres up to this point, Casablanca was about to become known as a

"disco label" that, by the way, also had stars like Kiss and Parliament.

It was about this time, the last few months of 1975, that some critical decisions were made at

Casablanca that would affect the future of Casablanca and even pop music in general. Neil Bogart had

met Italian-born artist/producer Giorgio Moroder, who with his partner Pete Bellotte, had set up shop in

Munich, Germany, running their label called Oasis. Moroder and Bellotte were mixing dance music for

European audiences, music that was played in dance halls (discotheques) across the continent. The

music - tagged "Euro-Disco" eventually - caught Bogart's attention. Bogart agreed to distribute the Oasis

label here in the US. The first single Moroder offered was a disco record by Boston-born singer Donna

Summer called "Love to Love You" [Oasis 401], a suggestive if not downright erotic dance groove. When

first released, it didn't sell quickly. Bogart played the new record for the dance crowd at one of

Casablanca's never-ending parties, and they demanded that it be played over and over so they could

keep in that groove. Bogart called Moroder in Germany and asked if he could come up with a much

longer version, and Moroder responded with a version that ran almost 17 minutes! He also requested

the title be changed slightly to, "Love to Love You, Baby." Bogart put the 17-minute disco blockbuster on

one side of the first Donna Summer album, and shipped promo copies to disc jockeys at clubs, making it

arguably the first 12-inch disco single. Sales from the clubs drove the single up the charts, where it

eventually made #2 (#3 R&B) in early 1976. This led to special long disco versions of singles, given to

deejays on 12-inch records, becoming standard fare in the music promotion world. Although they had

dabbled in several musical genres up to this point, Casablanca was about to become known as a

"disco label" that, by the way, also had stars like Kiss and Parliament.

Soon, the disco crowd wasn't satisfied to buy a short single version of the long songs they were hearing at their favorite night spot, and Casablanca responded by becoming one of the first labels to release commercial 12" singles. Acts such as Eddie Drennon, Paul Jabara, Pattie Brooks, the Sylvers or Frankie Crocker were not breaking down the pop charts with hit singles, but were big sellers in the Dance Record market.

Casablanca also went after licensing of many European disco productions: not only Moroder's out of Germany, but also French acts such as Love & Kisses, Sphinx, Santa Esmeralda, Alec Costandinos, Patrick Juvet, and Space.

But in addition to the decisions that promoted disco music and the internationalization of the US charts, the Casablanca staff started aggressively applying the unspoken motto of the company: "Whatever it takes." That is, whatever it takes to make hits on the chart, do it. They started aggressively pushing a couple of new singles a month, and in 1976-78, a majority of the singles Casablanca released made the charts somewhere.

In February, 1976, they had an easy listening song, "We Can't Hide It Anymore" by Larry Santos [Casablanca 844] enter the charts and eventually reach the national top-40 at #36. They released a new Parliament single, "P. Funk (Wants to Get Funked Up)" [Casablanca 852] to R&B stations and it did well, making #33. But the flip side, "Tear the Roof Off the Sucker (Give Up the Funk)" was also getting airplay, surprisingly from pop stations, so they reissued the same single [renumbered Casablanca 856] in April to pop stations, with "Tear the Roof Off the Sucker" being now pushed as the "A" side. The song was so different from what was being played at the time, and so clever, and so danceable, that it immediately shot to the top-20 on the pop charts, peaking at #15. It was the breakout record for Parliament, who followed that with many other pop hits.

For the rest of 1976 and 1977, the "big three" of Kiss, Donna Summer, and Parliament kept Casablanca

in the top 40 constantly. In the fall of 1977, Bogart added another theatrical stage act (Kiss and

Parliament were by now icons of stage theatrics). This time it was the Village People, who dressed as

men in various macho professions (policeman, fireman, Indian, biker, etc.) and played to many of the

crowds in gay discos in the New York area. Although their first single, "San Francisco (You've Got Me)"

[Casablanca 896] didn't chart, they came back in 1978 and 1979 with three straight disco blockbuster

classics: "Macho Man" [Casablanca 922, #25], "YMCA" [Casablanca 945, #2], and "In the Navy"

[Casablanca 973, #3]. Meanwhile, Donna Summer was also tearing up the charts with "Heaven Knows"

[Casablanca 959, #4], "Hot Stuff" [Casablanca 978, #1], "Bad Girls" [Casablanca 988, #1], "Dim All the

Lights" [Casablanca 2201, #2], and "On the Radio" [Casablanca 2236, #5]. By 1979, Casablanca was

the king of the disco sound. And they were selling over a billion dollars worth of records a year.

For the rest of 1976 and 1977, the "big three" of Kiss, Donna Summer, and Parliament kept Casablanca

in the top 40 constantly. In the fall of 1977, Bogart added another theatrical stage act (Kiss and

Parliament were by now icons of stage theatrics). This time it was the Village People, who dressed as

men in various macho professions (policeman, fireman, Indian, biker, etc.) and played to many of the

crowds in gay discos in the New York area. Although their first single, "San Francisco (You've Got Me)"

[Casablanca 896] didn't chart, they came back in 1978 and 1979 with three straight disco blockbuster

classics: "Macho Man" [Casablanca 922, #25], "YMCA" [Casablanca 945, #2], and "In the Navy"

[Casablanca 973, #3]. Meanwhile, Donna Summer was also tearing up the charts with "Heaven Knows"

[Casablanca 959, #4], "Hot Stuff" [Casablanca 978, #1], "Bad Girls" [Casablanca 988, #1], "Dim All the

Lights" [Casablanca 2201, #2], and "On the Radio" [Casablanca 2236, #5]. By 1979, Casablanca was

the king of the disco sound. And they were selling over a billion dollars worth of records a year.

Ironically, the decisions that made Casablanca successful in 1975 eventually led to their demise. It was in 1977 that Bogart sold half the company to an international conglomerate, PolyGram Records. They viewed Casablanca as a money machine, but actually this was not the case. Sure, they were selling tons of records, but the "whatever it takes" approach to selling them often meant that the promotional parties and such, along with the extravagant lifestyle of the staff, cost more than the records were bringing in. Almost paradoxically, the more success, the deeper in debt they got. PolyGram proved to be somewhat of an absentee landlord halfway around the world, not paying particularly close watch on the bottom line, choosing to delight instead in the gross sales numbers.

They had four star acts, Donna Summer, Kiss, Parliament, and the Village People, two of which were clearly identified with the disco craze. By 1980, Kiss, although still a substantial seller, had cooled off somewhat, and George Clinton of Parliament was busy with other projects for other labels, like Funkadelic for the Warner label. Other occasional big sellers, like Minnesota-based Lipps, Inc., who scored a #1 single in early 1980 with "Funkytown" [Casablanca 2233], were clearly also associated with disco. The decision to be king of disco music came crashing down in 1980, when the record-buyers tired of it, and of the music industry in general. In 1980, disco essentially died, and the record industry went into a deep slump in sales.

In early 1980, PolyGram was getting fidgety. Their financial types were feeling like there was something wrong at Casablanca, that the enormous revenue was being spent as fast as it came in, but they couldn't really tell from afar. So PolyGram bought the remaining 50% of the company and told Neil Bogart to take a hike. Bogart used the proceeds to set up a new label, Boardwalk.

Now PolyGram, with a slew of corporate types who had not run the day-to-day operations of a record

company, not to mention were located mainly in Europe, realized the extent of the problem they had just

bought. Disco was dying, the industry was tanking, and they had just bought a company that was tens of

millions of dollars in debt. Donna Summer, a legitimate singing star who could easily sing non-disco

material, unfortunately left Casablanca for Geffen Records in mid-1980, and with the plug pulled on the

other disco artists, Casablanca scrambled to sign some new talent. Well, some known talent,

anyway. They got a few hits in 1980-81 from signing music veterans Mac Davis, the Four Tops, the

Captain and Tennille, Tony Joe White, the Pure Prairie League, Dr. Hook, and Dusty Springfield, but it

was near the end of the chart career for all of these artists, and it didn't fill the gigantic hole left by the

departure of Donna Summer and the demise of disco. PolyGram poured millions into the company, but it

didn't even break even until 1983, when the soundtrack album from Flashdance became a huge

international hit. By 1983, though, Casablanca was a shell of its former self. Of their two remaing star

acts from the early days, Kiss eventually left for Mercury Records, another of the PolyGram companies,

and Parliament just stopped having hits.

Now PolyGram, with a slew of corporate types who had not run the day-to-day operations of a record

company, not to mention were located mainly in Europe, realized the extent of the problem they had just

bought. Disco was dying, the industry was tanking, and they had just bought a company that was tens of

millions of dollars in debt. Donna Summer, a legitimate singing star who could easily sing non-disco

material, unfortunately left Casablanca for Geffen Records in mid-1980, and with the plug pulled on the

other disco artists, Casablanca scrambled to sign some new talent. Well, some known talent,

anyway. They got a few hits in 1980-81 from signing music veterans Mac Davis, the Four Tops, the

Captain and Tennille, Tony Joe White, the Pure Prairie League, Dr. Hook, and Dusty Springfield, but it

was near the end of the chart career for all of these artists, and it didn't fill the gigantic hole left by the

departure of Donna Summer and the demise of disco. PolyGram poured millions into the company, but it

didn't even break even until 1983, when the soundtrack album from Flashdance became a huge

international hit. By 1983, though, Casablanca was a shell of its former self. Of their two remaing star

acts from the early days, Kiss eventually left for Mercury Records, another of the PolyGram companies,

and Parliament just stopped having hits.

Although Casablanca still exists today as a label imprint, for all intents and purposes, it was swallowed up by PolyGram. The singles on Casablanca under the PolyGram consolidated numbering system stopped in 1986. Since then, the label has essentially been used for reissues and compilations from the glory days.

Neil Bogart ran the Boardwalk label for a couple of years, but sadly died from cancer in May, 1982, at the age of 39. His Boardwalk label struggled on for about a year, then folded.

We would appreciate any additions or corrections to this discography. Just send them to us via e-mail. Both Sides Now Publications is an information web page. We are not a catalog, nor can we provide the records listed below. We have no association with Casablanca Records. Should you be interested in acquiring albums listed in this discography (all of which are out of print), we suggest you see our Frequently Asked Questions page and follow the instructions found there. This story and discography are copyright 2006 by Mike Callahan.

Casablanca Records Story

Casablanca Records Story On to the Casablanca Album Discography, Part 1 NB 9000

series and Special Products Issue (1974)

On to the Casablanca Album Discography, Part 1 NB 9000

series and Special Products Issue (1974)

On to the Casablanca Album Discography, Part 2 NBLP 7001

to NBLP-7099 (1974-1978)

On to the Casablanca Album Discography, Part 2 NBLP 7001

to NBLP-7099 (1974-1978)

On to the Casablanca Album Discography, Part 3 NBLP 7100

to NBLP 7199 (1978-1980)

On to the Casablanca Album Discography, Part 3 NBLP 7100

to NBLP 7199 (1978-1980)

On to the Casablanca West Album Discography

On to the Casablanca West Album Discography

On to the Chocolate City Album Discography

On to the Chocolate City Album Discography

On to the Oasis Album Discography

On to the Oasis Album Discography

On to the Parachute Album Discography

On to the Parachute Album Discography

On to the 20th Century Album Discography

On to the 20th Century Album Discography

Back to the Discography Listings Page

Back to the Discography Listings Page